It was bound to happen sooner or later. Living a life as an expat with a family trailing around after you isn’t a sustainable long-term solution. Realistically kids need to go to school, make friends, find a place in the world. Living in Singapore is challenging from that perspective and the truth is that the cost of international schools is eye-watering. Running through the finances showed that as the kids got older, and school fees increased, we would soon hit the point where we simply couldn’t afford to stay in Singapore.

So if we were going to move, where to? The next move could likely be the last (although we’ve always said that with each and every move) so it should be somewhere to finally settle down with our very own mythical “forever home”. We already owned property in the UK, but with a backdrop of Brexit, this didn’t feel like the best destination for us. Time to sell up and exit.

So that left Australia. My wife proposed a move to Tamborine Mountain near to the Gold Coast in Queensland. It’s not far from where she grew up, and critically it has very highly rated state schools. All that would be needed was to ensure that we fell into the catchment area. Turns out that this was easier said than done if you had aspirations to build a house as there isn’t a large amount of land on top of the mountain and large proportion of it is already developed. Yet fortune smiled on us and we were able to secure a piece of land on the mountain that hadn’t been developed and yet was close to the schools.

Which leads me to the point of this blog. My family is moving to Australia and we’re going to build a new house. This is a path that many many people have been down before us and I’m sure we’re not about to trailblaze anything fantastically innovative. Yet in the best traditions of “Grand Designs” it seems worthwhile to keep a diary of the build, if for nothing else so that we can look back and remind ourselves how we got to this point.

Setting the Objectives

Well it’s safe to say that if I was going to embark upon a personal project, I would need to bring some experience from my days working at Independent Project Analysis to bear. One of the most important elements that is associated with failure of large projects is that those projects had unclear objectives. It’s pretty hard to fathom just how a project spending hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars could have unclear objectives, but believe me, it happens. I was adamant that we were not going to fall into the same trap.

We wrote out our objectives for the build. I’m not joking. I actually sat down with my wife and we discussed what we wanted. I even started a document to record our thoughts and choices. If you’re going to do a job, you may as well do it properly as the saying goes. There were three main parts to these objectives:

-

Passive House Principles: I must admit that my vision was driven largely by some school science projects I’d done when younger. I’d had a fascination with solar energy and had researched (painstakingly I might add as this was in the days before the internet) various technologies and methods to optimise passive heating and cooling through building design. At the time this was of course just research on paper, but it sparked a desire to one day, perhaps, have a chance to build something that turned the dreams into reality.

-

Practical Family Layout: My wife was looking for practicality for a large family and day to day living. A large kitchen with an island, double ovens, open plan living area opening out to a large garden, individual bedrooms for the four kids etc. Sensible design. Nothing fancy. OK, I’ll admit that I really didn’t have much to add in this area. Or at least I didn’t until I was told that I could design a home cinema room.

-

Cost Efficient Design: The final objective was that it would need to be cost effective. We both agreed on this point albeit for different reasons. My wife, being the responsible half of the relationship, didn’t hesitate to remind me that our pool of funds to build a house was not bottomless. I on the other hand was adamant that we could take a leaf from the Twinza playbook where I was working on oil and gas projects to drive down the cost of field developments. This would involve a focus on design that was “good enough” to meet the requirements without the “gold plating” from a best-in-class solution. Of course I had no idea if this was even possible with house design, but it couldn’t hurt to try.

Visualising the Build Together

How do you go about finding a house design and builder to meet these objectives. I may one day truely regret this decision, but early on we decided that using an architect to design the house and then finding a builder wouldn’t be compatible with the third objective. The approach would undoubtedly meet objectives (1) and (2) with flying colours – but could we afford it?

Which placed the build in a quandry early on. How to mould the design to suit our objectives whilst keeping a tight rein on the costs? Our idea was to take an existing project home design and modify it, only slightly, to suit our objectives. This would allow us to take advantage of the lower cost of building materials and labour available to a project home builder. Through modification to a pre-existing design there would be much less work in comparison to creating a new home design from scratch and we would still be able to influence the design to suit our objectives. After all, “How hard can it be?”.

Well based on experience so far I’d stop short of an answer along the lines of “very” but definitely somewhere in the realm of “more than I thought”. The reason being that I had this strange notion that a project home builder was going to be able to modify everything just like an architect might take direction from a client. For small changes this is probably true. I gather that most people buying project home design will pick one they prefer, specify the exterior look and internal finishes from the builder’s range and just get on with the build. Perhaps this is a generalisation but it’s a conclusion I’ve drawn as our approach appears to be an outlier.

The Problem With Project Home Designs

I don’t mean to knock project home designs. They bring affordability to home design and if we’re honest there are so many pre-designed options available that it’s incredibly unlikely that there is going to be a similar model on your street or even in your area if you’re building a one-off on an existing plot of land. This doesn’t really hold true when buying a home in a new development as all modern home designs follow a tried and tested formula leading to suburbs that feel quite uniform. I won’t argue the aesthetics because most people will spend their time living in the house, at which point how all the houses in the neighbourhood look from the kerbside takes a back seat to how comfortable it is to live in the house.

It is here we find the problem. It is a misconception that Australia’s climate is always so warm and sunny that no attention need be paid to home design. Insulation, double glazing, windows facing the winter sun for warmth: these are concerns of designers in colder climates. Designing for climate is clearly irrelevant for Australia.

Designers and builders are not surprisingly in the business of making money. When clients are asking for larger homes, with more bells and whistles, at lower cost, it is inevitable that sacrifices need to be made. Those sacrifices are inevitably parts of the house that the client cannot immediately see. Why specify a higher grade of insulation when you only need to use the minimum necessary to meet regulations? Why use double glazing when you can have a larger window that lets in more light for the same price with single glazing? Why use an efficient electric heat pump hot water system when a gas hot water boiler is cheaper?

This is not to say that builders cannot build efficient houses. Of course they can. But the problem is that not everyone is asking for them and the standard home designs therefore do not include these additional cost items. All of which means that if you want an energy efficient design, then you had better know what you are asking for and why.

Bringing a Design to Life

Front end loading is a project concept whereby experience has shown that time and effort expended during the early parts of a project i.e. during the design, pay back many times in the form of savings that are achieved simply through avoiding problems during a project that might arise as a result of rushing into the build. As one project manager explained to me once, “it is far easier to change electrons in the computer than it is to change steel once you have built it”. This is the philosophy that we adopted for the planning stages of our house design.

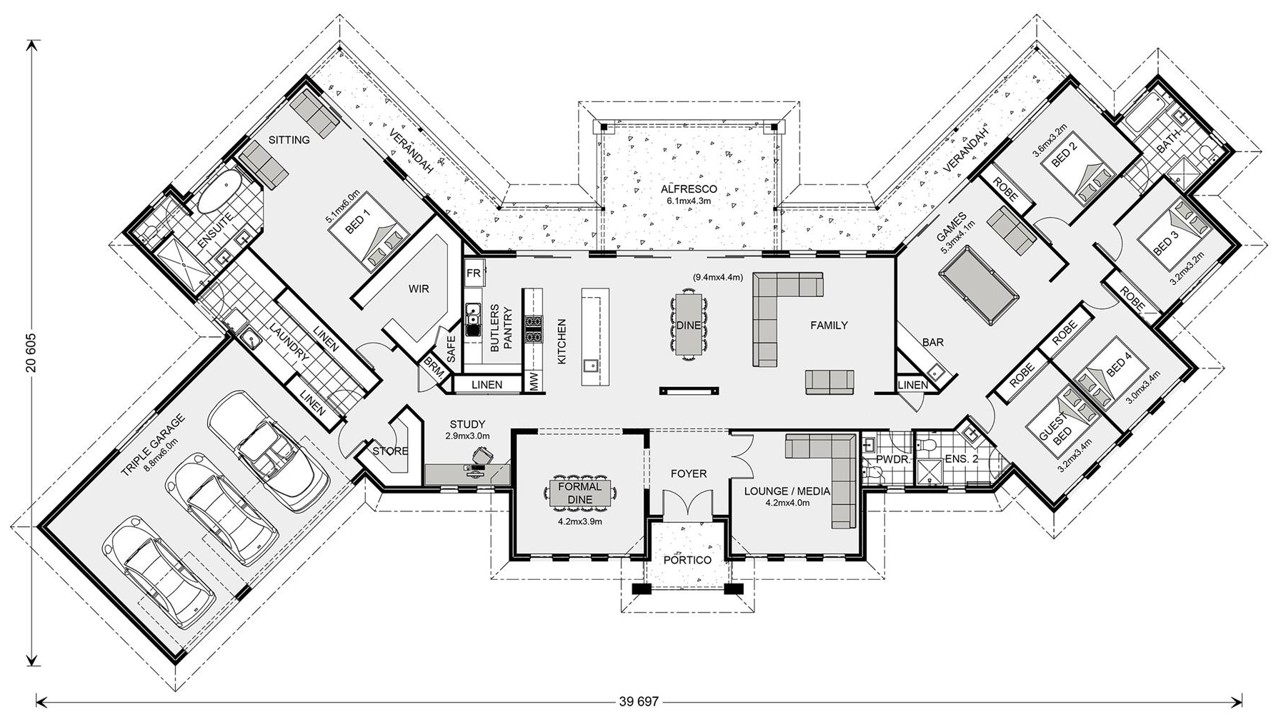

My wife undertook all of the initial work which largely involved studying different floor plans that are available from numerous builders on their websites. Eventually a design that appealed was the “Montville” design by the building franchise G.J. Gardner. This design featured many of the ideals enshrined in our second objective: the large open plan area, separate bedrooms for the kids in a separate wing of the house, a large kitchen etc.

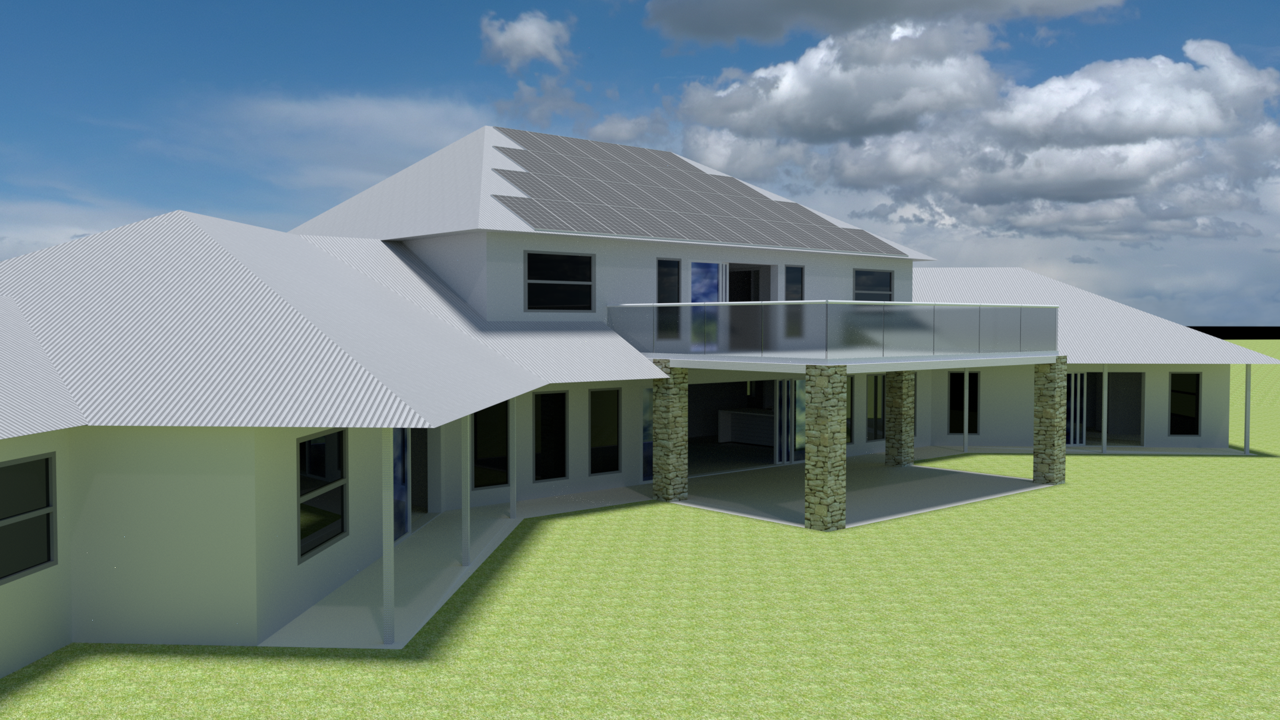

Through the wonders of modern computer visualisation, there was also a pretty impression what such a floor plan might look like when built. Impressive stuff.

At this point the sensible option would be to engage with the builder and get a quote for a build on your plot of land. Honestly, there is no need to do anything more. It’s an off-the-shelf standard design.

Instead what I saw was a glimpse into the world of 3D CAD and house design. The designs clearly existed in a three dimensional form and this was used to create the visualisation of the house. Would it be possible to recreate that? Would we then be able to modify the design once we had the 3D design?

Many years ago I had done some basic 3D modelling using the SketchUp program that was originally developed by Google. This was a free software that allowed for intuitive modelling of 3D objects. Out of curiosity I started looking into how to design houses using SketchUp and what I found was a wealth of information. Building a basic interior layout for a house is not that hard as it turns out. This was the start of the rabbit hole into which I was being drawn. Now I just had to try this out. Could I build a model of the Montville design and modify it? Much to my surprise, within a few days we had a useable model that could be used for discussion with the builder.

The initial modified design incorporated a second story and a wider atrium in the centre of the house to accomodate a staircase. In my mind these were minor changes. The footprint of the house had barely been altered. The flow of the rooms on the ground floor was identical.

During these early forays into the software, when still learning the basics of how to create surfaces and manipulate the model, it was apparent that the power of the tool lay not just in making the 3D model, but in using this model as a communication tool. Being able to see what was going on with the house design in real time meant that changes could be tested and incorporated very easily. What I learned was the limitation was rarely the software. It was the natural human tendency to resist change. Having laboured for hours giving birth to a virtual 3D model, the pain of being told I’d “got it wrong” was often agonising; sparking intense arguments over placement of a wall or whether an area had sufficient natural lighting. The power of the 3D model to provoke clear understanding on the one hand, and yet difference of opinion regarding the design on the other, is an aspect of technology I have never seen discussed.

One aspect that I wasn’t satisfied with was the ‘look’ of the model. SketchUp has many different styles that can be applied to the model when displaying it, but many of these styles end up looking very similar. It’s a trade-off between an accurate and believable representation of the model and the responsiveness and speed with which a computer is able to manipulate the model.

What I hadn’t appreciated was what was involved with the methods that are used for creating those photo-realistic visualisations that you commonly see. These don’t appear instantly but are instead rendered using a technique called ray-tracing (the same technique used to create CGI movies). To see what a difference this could make I exported the model into another free 3D modelling tool called Blender and created a render of the house.

The results were impressive given the speed (and not to mention inexperience) with which the house had been modelled. We had demonstrated it was possible to immediately get feedback on changes to the house design without needing to engage an architect or to have access to the original design files.

In later blog posts I’ll delve into how we’ve used this software to help communicate our designs to the builder and illustrate how the design has evolved in response to what we learn along the journey.

To conclude the introduction to our journey, I’ll make the observation that when we started out we were innocent regarding what we didn’t know. Putting together the initial 3D model and rendered image was surprisingly quick leading one to wonder why everyone didn’t do this. What I didn’t appreciate at the time was that I was merely scratching the top of the iceberg. There was much more to learn in the months ahead! As I have now realised, what I had done was accidentally take on the role of an architect. Sink or swim time…