Nearly a year ago I gave a presentation at an SPE workshop in Kuala Lumpur on the topic of selecting “appropriate scope”. This is a catchphrase coined by Twinza’s CEO, Huw Evans, and is a cornerstone of Twinza’s philosophy on project delivery. In the presentation I used elements of the Pasca A project to illustrate how significant cost savings can be delivered. These are a snapshot of the approaches that Twinza has employed during the recent oil industry downturn in order to keep the project on track for delivery. For Twinza the drop in oil price had the opposite effect to that seen in larger companies with shrinking budgets – in our case it was necessary to step up a gear in order to deliver a step change in project economics.

Also presenting at the workshop was my former boss at Independent Project Analysis, Rolando Gächter, with research on cost of offshore projects and whether more expensive “better” concepts really delivered better results. Both of us were invited to jointly present our talks to SPE Singapore a few months later, as both were complementary in their material.

This blog contains all the presentation slides that I shared with SPE, and some commentary for each slide.

Pasca A Case Study

Source: Twinza Oil, SPE

The basis for the talk is the field development planning undertaken for the Pasca A field offshore PNG which is operated by Twinza Oil. In the context of the SPE workshop, the objective of the talk is to demonstrate that value can be delivered in the early phases of a project when the concept is being considered. During an era of high oil prices (prior to 2014) there is a perception that delivery of projects has become ‘lazy’ and the effort has focused more on delivering projects to a fast schedule rather than managing the project cost or reservoir performance. I often like to make the observation that in an ideal world, the perfect project would be fast, cheap and high quality. In the real world, you get to pick two. The car analogy works well here. If it’s fast and good, it won’t be cheap. If it’s fast and cheap it won’t be good. And finally, if it’s cheap and good, then it’s probably not going to be fast. Of course, those of you with experience of supercars will also know that fast cars are not cheap to buy, or to run. They might superficially look great, but they tend to be unreliable leading to high running costs. It’s sort of the same way with projects. If you try to deliver too fast then all sorts of problems will come back and bite you later on, leading to higher costs and poorer performance. Personally I prefer projects that focus on delivering production, reserves, at low cost and accept that it takes as long as it will take.

Source: Twinza Oil

How am I qualified to give this talk? Between 2010 to 2014 I was working as a Senior Project Analyst at Independent Project Analysis (IPA) where I had the privilege of reviewing more than 100 projects in various phases from early conceptual development through to several years after start-up. This experience and the insight from IPA’s extensive project database and research, provided an invaluable understanding of what contributes to project success, what puts projects at risk, and where the myths lurk in the grey areas in between. At the time I gave this talk I had recently started at Twinza Oil and had responsibility for shaping the concept for the Pasca A field development. What a great chance to put into practice everything I had learned over the years.

Source: Twinza Oil, DRL Engineering

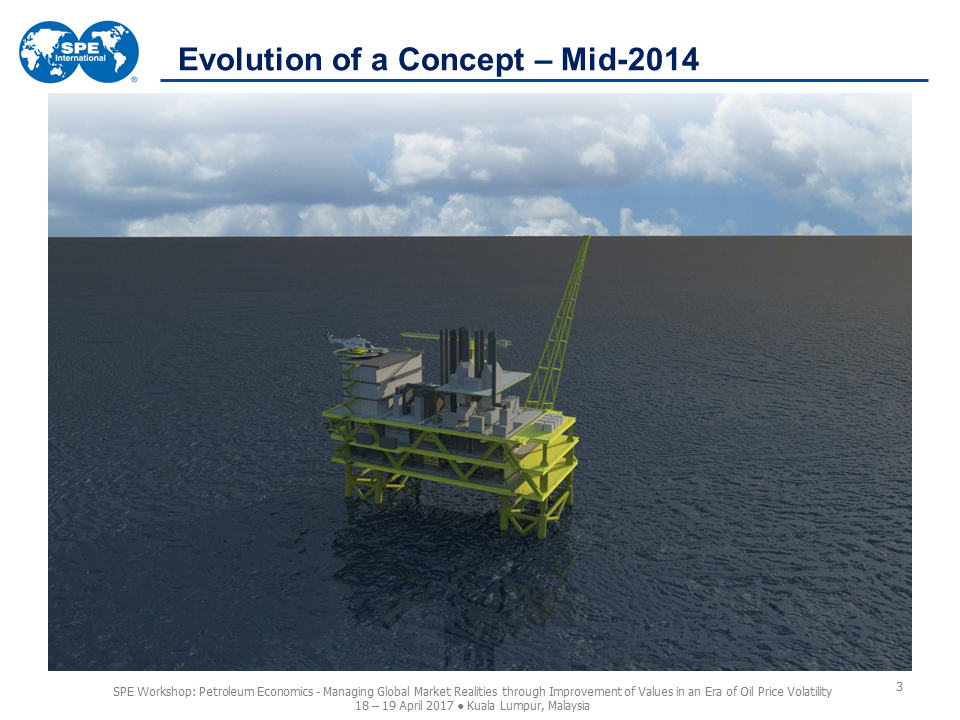

What did I find when I started at Twinza Oil? The Pasca A field is a gas-condensate field in a Miocene carbonate reef, approximately 2,200 metres true vertical depth, located 100 km offshore at about 100 metres water depth. A conceptual artist impression of the surface facilities is shown in Figure 3. Resource volume estimates at the time were around several hundred bcf of wet gas, about half of which was liquids in the form of condensate and LPG. An early concept development had been undertaken with a view to use a conventional fixed platform. Running through the economics, everything looked fine. There wasn’t anything inherently wrong with the chosen concept, except that as 2014 rolled to a close, the oil price started to fall.

As everyone in our industry knows, it kept falling through 2015 and never really recovered. Certainly at the time I gave this talk it hadn’t recovered. Since the Pasca A field was effectively the only asset at Twinza, this placed a huge amount of pressure on the project team to ensure that the development of the field remained viable. As oil prices fell below $50/bbl, the project was still commercial, but at prices started to approach $20/bbl, the concept was no longer viable. A change in approach was needed.

Source: Twinza Oil

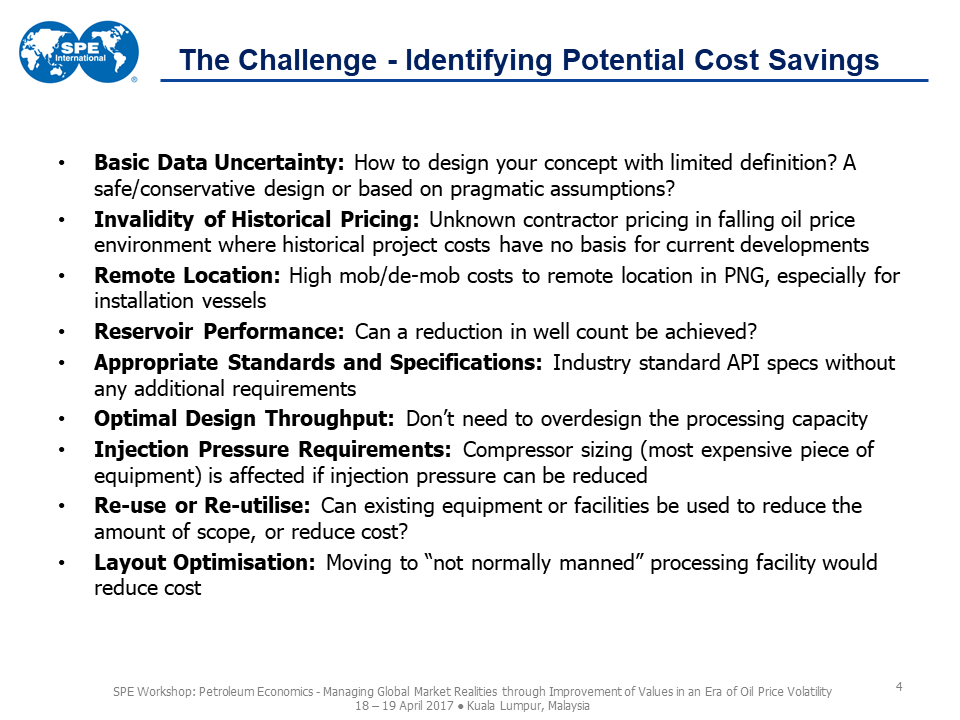

“Necessity is the mother of invention”, as the saying goes. Faced with the need to keep the project development viable, all aspects of the project were considered and challenged. I found it surprising how many areas we were able to identify for improvement. Figure 4 lists the main areas identified at the time.

-

The first point concerns the philosophy adopted towards the design. Every project has data uncertainty that must be accomodated into the design. Very often projects will make assumptions to bridge that data uncertainty and pay the price later when it is discovered that the data assumption was wrong. At IPA I recall hearing about a certain LNG plant that utilised air coolers in a constricted space. For the coolers to work effectively it was necessary to orient them appropriately to the prevailing wind direction, and understand the ambient air temperatures etc. Rather than go through the time consuming process of actually measuring the data themselves, apparently the project team asked the local weather man and based their design on this information. When the plant finally started up several years later, it was discovered that the coolers were not optimally oriented, and because of the site’s layout constraints, it wasn’t possible to easily reconfigure them. The consequence is that they were left with an LNG plant that didn’t perform as efficiently as it should. That means it was costing them money – a lot more than it would have cost to gather the data using a pretty cheap anemometer and thermometer.

The flip side of the coin then seems to be that a project team should be aware that missing basic data can be costly, and take a conservative approach to design. But building to the worst case scenario, as will be shown, can be costly. A better approach is to look at the data uncertainty and assess where obtaining data would be more cost effective, and to pragmatically think about the consequences for design arising from data uncertainty. The example later in this presentation should make the principle clear.

-

Early facility cost estimates are often put together using a factored cost approach. This relies upon the use of historical data to build up a cost estimate for a similar but slightly different plant. At the simplest level, this can be conceptualised as a dollar per ton approach. I design my facility and find it is going to weigh 1,000 mt. In the past few years, the average all-in cost for similar facilities was $25,000 per mt. Therefore I might expect my facility to cost $25 million. Whilst in practice the application of historical rates to project quantities is much more granular; the principle error in the methodology in the context of the Pasca A project is unchanged. That error is that all the historical price information was generated for projects that were executed during a high price environment. Typically as demand rises and falls, these rates will lag slightly, and provide a good reference. As long as projects continue to be executed, there is a conveyor belt of data that will keep the database of recent rates fed. So what happens when projects stop like they did at the end of 2014? If no-one is undertaking projects anymore because capital budgets have been slashed, what is the cost to a project that does proceed? The historical costs suggest that the cost is very high. Twinza didn’t believe these historical rates were relevant in a market where fabrication yards were hungry for work. By approaching the market it was discovered that the costs materials and labour had both come down. In other words it is necessary to be pro-active in developing cost estimates and not merely relying on what has been done before.

-

When dissecting the historical cost estimate for Pasca A it was discovered that the mobilisation and demobilisation costs for installation vessels to the relatively remote location of Papua New Guinea was very high. Furthermore, once mobilised these vessels would be needed to sit around waiting as they couldn’t just be called upon when needed on an ad-hoc basis. The need for these vessels was a consequence of the conventional platform design which used a floatover topsides which is lowered onto a fixed platform. Twinza modified the concept to use a self-installing platform (SIP) or jack-up / mobile offshore production unit (MOPU) to everyone else in the industry. This has the benefit that the platform houses the equipment necessary to install itself at the correct location, thus eliminating the expensive installation vessels required for the alternative fixed platform concept entirely.

-

The original concept called for three production wells and two injection wells. Five wells might not sound like many, but if that number could be reduced, to say three (two producers and one injector) then that would be a considerable cost saving. When examining the basis for five wells, it was found that the main reason was related to redundancy. If a well failed then production could still continue with other wells. Fortunately reservoir performance was so great that production was definitely possible with just three wells. The wellhead platform has been designed with spare slots so that if there is a major problem and more wells are needed, then they can be drilled. However, that is a possible issue for the future. Today we need to present a viable cost-effective development solution, and the inclusion of redundant back-up wells does not meet that criteria.

-

Standards and specifications, it has to be said, are a particular hobby horse of mine. They are there to ensure safety and consistency in design, to prevent mistakes from being repeated, and to ensure hard won knowledge is transferred into future designs. In general I don’t have a problem with the principle. Yet it is widely recognised (albeit not aired out loud in public much) that our industry has a problem with excessive standards. Many companies not only adhere to the American Petroleum Institute standards, but layer on top of those their own design practices that must be followed. For example, no longer can you use the standard paint, but it must also conform to exacting toxic chemical specifications which go above and beyond those normally considered acceptable by the industry. This adds to cost in return for a dubious benefit (if the existing standard is good enough why do you need to exceed it?).

More critically this can lead to farcical situations. I’ll never forget one project describing to me how their contractor had called up the project to ask which of the company’s additional standards they didn’t have to follow. The project team told them, naturally, that they needed to follow all of them. Except this was a problem. As the contractor explained, in the engineering version of a joke, that if this was the case then the only material they could use would be unobtainium and could the project team lay their hands on some of this material? Humour aside, the very real issue is that the contractor was dealing with hundreds of additional small design practices. Each on their own was probably introduced in response to some minor lesson learned e.g. for better reliability in future we should ensure the material meets at least this criteria, for better safety this manufacturing technique is better, for corrosion resistance we want a higher level of protection so we’ll need this special alloy … oh, and the CEO has asked that it comes in the same colour as the company logo. That last one isn’t actually a joke, it really happened on one project! The point is that each little additional requirement seems small. The combination of finding a material to satisfy them all at the same time is exponentially more expensive and in some cases outright impossible. The problem is that there is no arbiter of what standards to apply or not. The corporate guidelines must be followed and it is a brave engineer that suggests they don’t need to adhere to them.

As will be shown in our upcoming example, a willingness to challenge the industry standards, as well as corporate design practices, can yield cost savings. Note that I am note advocating ignoring the standards and adopting a cavalier make-it-up-as-we-go-along mentality. Far from it. What I’m proposing is that a critical engineering mindset should be adopted towards all aspects of the design, and to understand why a standard is worded in a particular manner rather than blindly accepting it as gospel.

-

Design capacity is a classic problem for the oil industry. Data from real world projects show that on average, projects fail to meet 100% of their target production rates during the first year. This means that the facilities were designed too large and money could have been saved by designing to a lower rate. Of course the problem is that optimism bias affects the reservoir interpretation and when a more aggressive or higher production profile is run through the economic model, the project looks better. The sad truth is that better looking projects get sanctioned. I often wonder how many great projects are out there, unsanctioned, because their project teams took a realistic approach to their assumptions.

Twinza’s philosophy was to take a modest approach to the design production rate. If the field ended up larger than planned, then production would just continue for longer. A far better outcome than spending more than necessary and then finding out that the field was smaller than this optimistic assessment.

-

Communication between disciplines is essential. This goes beyond just talking to each other. It means team members need to have a basic understanding of the other disciplines so that they can speak the same language. The importance of this became evident in one aspect of the Pasca A project related to tubing size. The well completions engineer was resisting a move to a larger tubing size as it wasn’t needed to achieve the design production rates. A larger tubing size would add to the material cost for the completion, so naturally this was a logical conclusion. Except I was also aware at the time that we had a high injection pressure requirement and a larger tubing size would reduce this injection pressure. Lower injection pressure = smaller compressor. Compressors are expensive, and being able to reduce a compressor size was a large cost saving. I picked up the phone and checked with the facilities engineers that the lower injection pressure associated with larger tubing was real. Cost saving for compressors is larger than cost increment for tubing. Decision made. One afternoon.

Our consulting engineers remarked to me many months later that this decision would typically take many weeks or more in a larger company, if indeed the decision even received any air-time. To this day I don’t know if that is true or not (I sort of hope that it isn’t). What it does emphasise is the importance of being able to communicate between disciplines. Without a technically-informed high level view of the project, important relationships between different disciplines in a project will be missed.

-

Reduce, reuse, recycle. A common mantra in the home. Equally important and relevant in industry. Sure, new is shinier and probably comes with some superficial warranty period. It’s not always necessary. Conversion of tankers into floating production storage and offtake vessels is an extreme example of repurposing, yet it is frequently done and can save cost if done carefully. I do caveat this carefully though as discovery work when undertaking revamp activities is a bane of our industry.

-

Layout optimisation might seem like an odd one. How on earth does this save cost? Again, it comes down to understanding the interaction between different aspects of the design and the standards. In this case, the requirements for manned facilities are much more onerous than for unmanned, or not-normally manned facilities. This is as it should be. Piper Alpha taught the industry that people living next door to a hydrocarbon processing plant can be a tragic mixture. So rather than putting people and the plant next to each other, why not separate them? Put the accomodation on a spread-moored floating storage and offtake vessel next to the self-installing platform, and provide access via a walk-to-work gangway. By no longer requiring a multitude of items related to the proximity of processing facilities next to accomodation space, it suddenly lowers the cost for the process topsides. Credit where credit is due … thanks to Hassan Basma for the suggestion.

Source: Twinza Oil

It’s all well and good to trumpet Twinza’s achievements. How can such an outcome be replicated on other projects? What pearls of wisdom do we have too share that can help others looking to reduce their own project costs?

Our belief is that it comes down to the team members and the culture that is established within that team. All the statements shown in Figure 5 could easily have been lifted from any management guru’s textbook. So what I will say is that it’s one thing to “talk the talk”, it’s quite another to “walk the walk”. Every team member on our project team will probably describe it differently. From my perspective the key ingredient is that if you want others to follow, you must lead by example. That means listening to others, acknowledging your own mistakes (visibly), being prepared to take responsibility for the decisions that need to be made and making them rather than trying to kick the can down the road or cover your arse. With clear objectives and a willingness to do the best possible, not because the team has been told to, but because they want to, any team can excel. Sadly, too aften a “tick the box” mentality to deliver a project sets in.

At IPA I came across two project teams that epitomised these two extremes. The first team were faced with a challenging project. They had decided to go above and beyond the minimum corporate requirements for some aspects of their project, because they believed it was necessary to reduce the project risk. At the same time they were not afraid to seek waivers for some requirements they felt were unnecessary in their circumstance. The most revealing part came when I needed to interview the team on some reservoir engineering matters. Their reservoir engineer wasn’t available so I ended up interviewing the facilities team lead. This guy was not a reservoir engineer, but he knew everything that mattered about the reservoir and in particular how the uncertainties in the data would affect the wells design, facilities design and project objectives. I was astounded. That is a level of team integration that we try to achieve at Twinza.

At the other end of the spectrum was a project team where the answer to any challenging question lay in, “you don’t understand – we must do it this way because of company policy”. They had taken work done on previous projects and modified it to suit their own project, which created a suitable veneer of respectability. Certainly, where their project process required that they had completed certain activities as evidenced by specific deliverables, they were able to tick each and every box. Not one project team member was able to articulate why they needed to do this work or its relevance to other disciplines in the project.

So perhaps these two examples are illustrative of difference company culture? Sadly no. Both project teams were from the same company, in different countries. I can only draw the conclusion that it’s not the company policies or culture to blame. It’s almost luck of the draw when assembling the team. A good team will spur each other on and get stronger and stronger. A weak team will gradually rot away. Ultimately “people do projects, not processes”. The project organisation must not neglect the cultures that arise in each project team and try to foster the best attitudes across all their teams. Whilst easier said than done, that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.

Source: Twinza Oil, Aquaterra, 2H Offshore

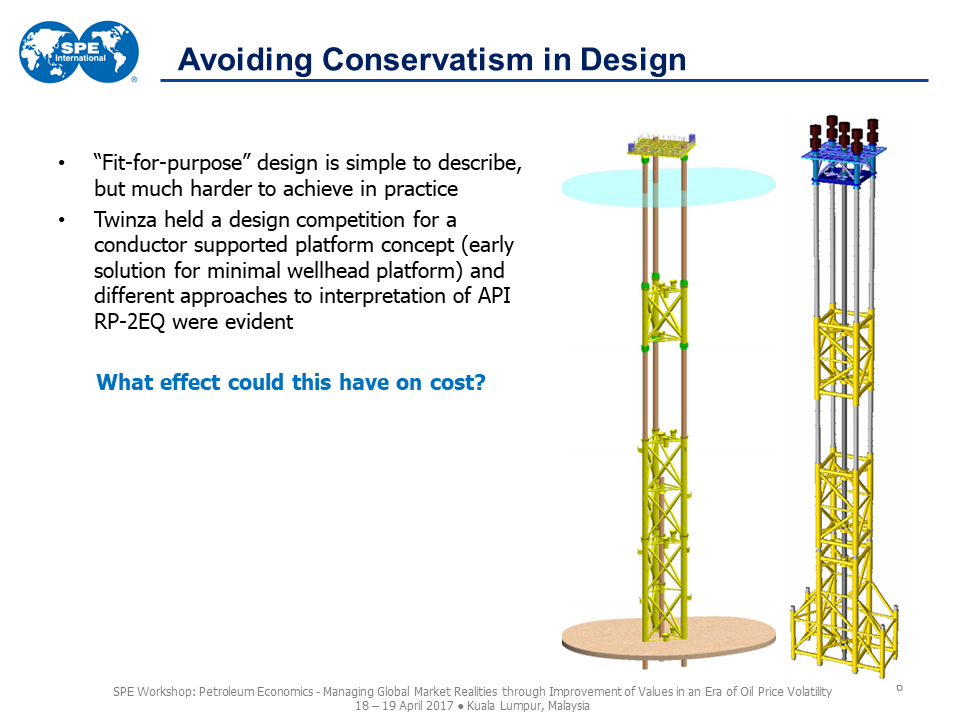

Earlier I mentioned that I would have a specific example to illustrate some points. Let’s turn our attention to the wellhead platform that Twinza proposed to use for the revised concept. This was to be a minimal design with no additional functionality other than it supported wellheads. Two companies had “conductor supported platform” concept whereby the well conductor string also functioned as the platform jacket and piles. When it comes to “don’t build more than you need”, having materials that serve several functions at the some time is masterfully efficient.

So Twinza ran a design competition. The basic requirements were for a platform that could host a minimum of five slots and stand unsupported for at least a year before being braced to an adjacent jack-up platform. The responses from two companies are shown in Figure 6. Even without any expertise in facilities design, it is evident that the design on the left is lighter (and thus cheaper) than the design on the right. In fact the cost of the design on the right is around double that on the left. Given that both companies were given the same basis of design, how could such a massive difference in cost arise.

Through a clarification process and face-to-face discussion it was identified that the answer lay in the interpretation of one industry standard in particular: RP-2EQ. This concerns seismic design procedures for offshore structures. Specifically the aspect of this standard that relates to the two design concepts proposed, is the maximum deflection that would occur at the platform during an extreme seismic event at the platform location. One contractor in the design competition had followed the standard precisely, the other had considered the rationale behind the standard and decided that an exemption could probably be sought and therefore had ignored this criterion. What specifically could lead to such a difference in design and why would it matter?

The aspect of this standard that leads to the difference is a consideration of the maximum likely seismic event at the offshore structure location. The lateral deflections at the platform should be less than a metre during such a maximum seismic event so as to reduce the risk of throwing a person overboard. If a structure does not meet the published standards, then it will be very difficult to obtain insurance, so designing and building to standards is very much normal practice. This appears a sensible objective until you consider the following:

- The platform is designed as a minimal wellhead platform which will be unmanned and eventually braced to a jack-up platform. During its unsupported period there will be no personnel on the platform. Therefore reducing the risk of throwing a person overboard during an extreme seismic event is somewhat redundant.

- The standard in question extended an earlier standard on earthquake design for specific localised areas to a worldwide basis. This suffers from the inherent limitation that some areas have better data than others. In the case of offshore Papua New Guinea, the maps in the standard showing the maximum earthquake strength that should be designed to are a clear extrapolation from regional data and there is even a note in the standard that the data should be verified. Comparison of these maps against the PNG seismicity maps shows that the area in which the Pasca A platform is located is in fact a very low seismicity area.

Taking this into consideration, one contractor had reasoned that an engineering argument could be made that this particular standard should not apply and it was very likely a waiver could be obtained. Furthermore, the argument was made that even if it were to apply, there was a very strong probability that site-specific data would indicate the earthquake strength that needed to be designed to was much lower than that indicated in the standard. Remember when I mentioned earlier about the importance of challenging industry standards and getting the correct basic data upon which to base your designs? Well this is a case in point, and the cost saving that results from allowing a less stiff platform jacket is half. This is a huge saving.

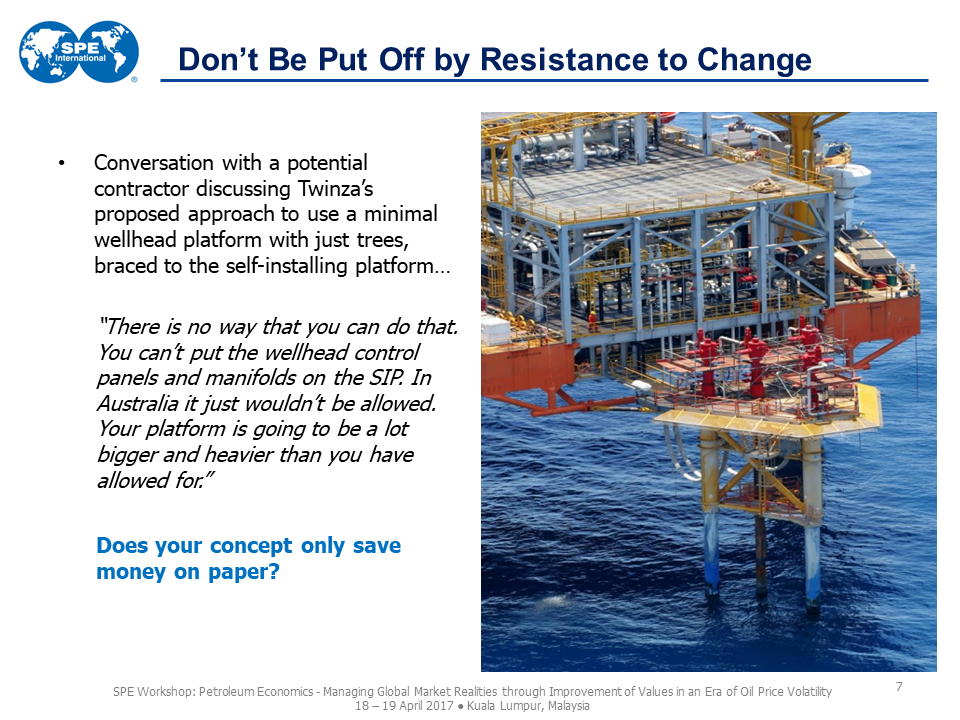

Source: Twinza Oil, Santos

When taking the pragmatic route, a project team must be prepared for a variety of ‘expert opinions’ that will inevitably seek to scold the project team for breaking with the orthodoxy. In the case of Pasca A, having selected the cheaper design concept for the wellhead platform, the project team was confidently informed by a third contractor that the design simply was not possible. Such a minimalist wellhead platform with just wellheads and very little else simply couldn’t be contemplated. There would need to be safety systems, a helideck, temporary refuge etc. All of the other requirements we hadn’t considered would add to the platform topsides weight and hence the overall size of the platform. In short, we were dreaming and it couldn’t be done.

Except the so-called expert was wrong. How do we know? Well Figure 7 shows a real-world minimal wellhead platform – Santos’ Oyong field in Indonesia. It just so happens that this is a conductor supported wellhead platform with just wellheads on the topsides, which is braced to a jack-up platform on which the main processing topsides are located. It is exactly the concept Twinza is considering. If the expert is correct, then how on earth did Santos manage to build such a concept?

Source: Twinza Oil

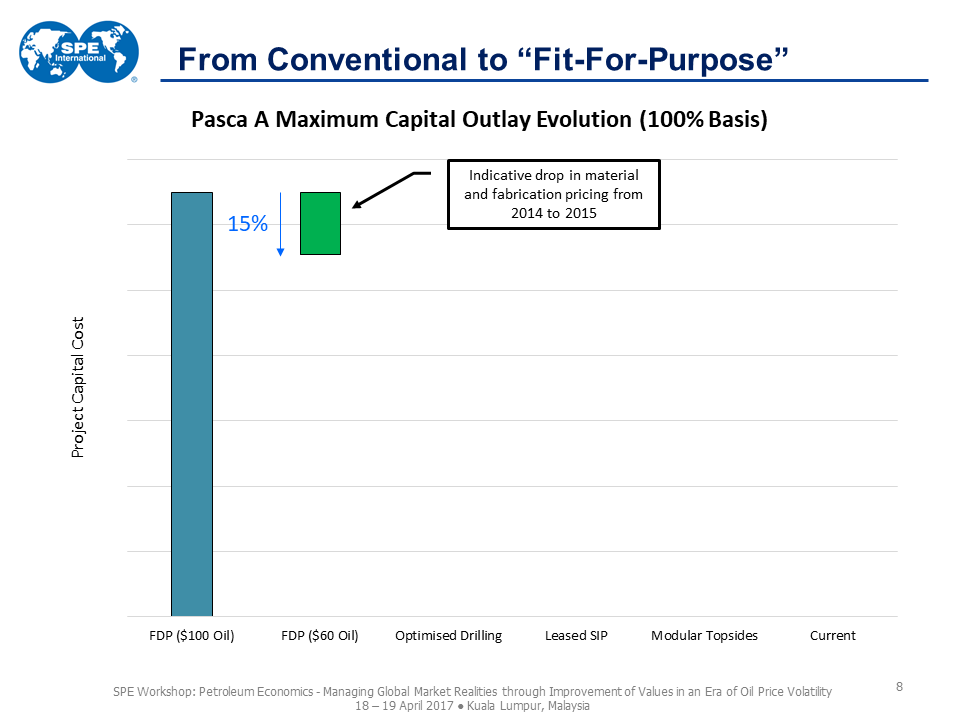

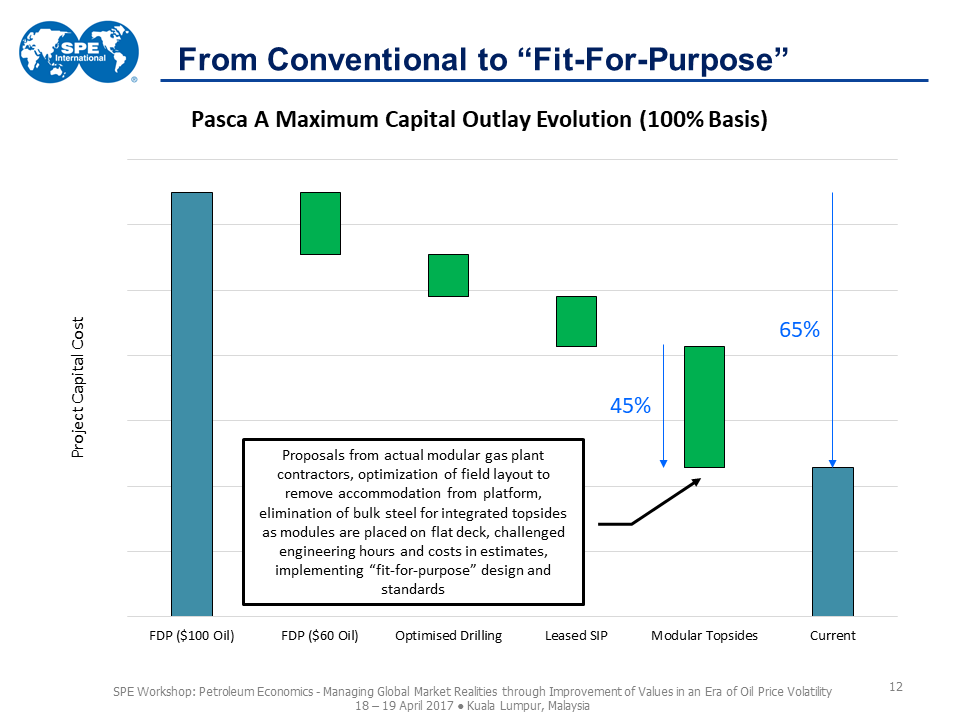

Having outlined some principles of “fit for purpose” design and illustrated one of those principles more closely, let’s now look at what sort of cost saving can be achieved for a project. I’ve been back over the cost estimates for Pasca A prior to and after this cost exercise and broken the cost savings into different categories.

First off, in Figure 8, we have the “do nothing” situation. The original cost estimate would have reduced by roughly 15% anyway as a change in market conditions related to lower steel and equipment pricing, a reduction in labour rates and a generally more cost competitive fabrication environment. Of course, without many projects actually being executed, one could ask if this is a mere mirage?

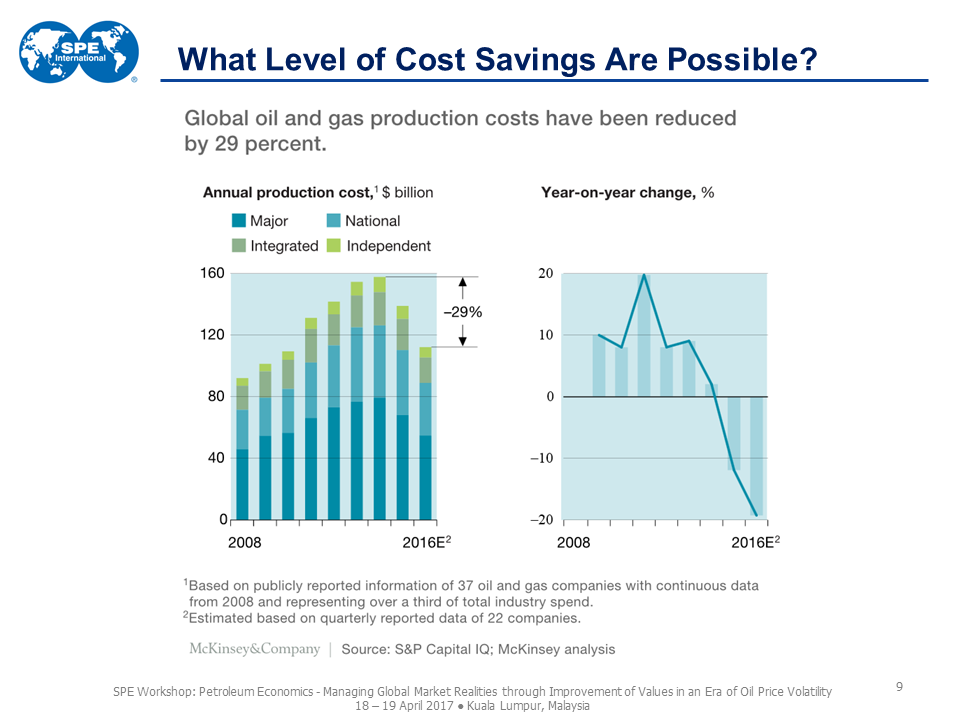

Source: Twinza Oil, S&P Capital IQ, McKinsey

Well other industry data suggests that it is real. Shown in Figure 9 are data relating to the expenditure by industry on capital projects. There is a projected decline in expenditure of 29 percent. A cynic might note that the comparison here is not strictly apples to apples. I would point out that since the analysis was performed, real market conditions and bids received by Twinza have proved that, if anything, we were too conservative. The cost saving is more than 15 percent on our project.

Source: Twinza Oil

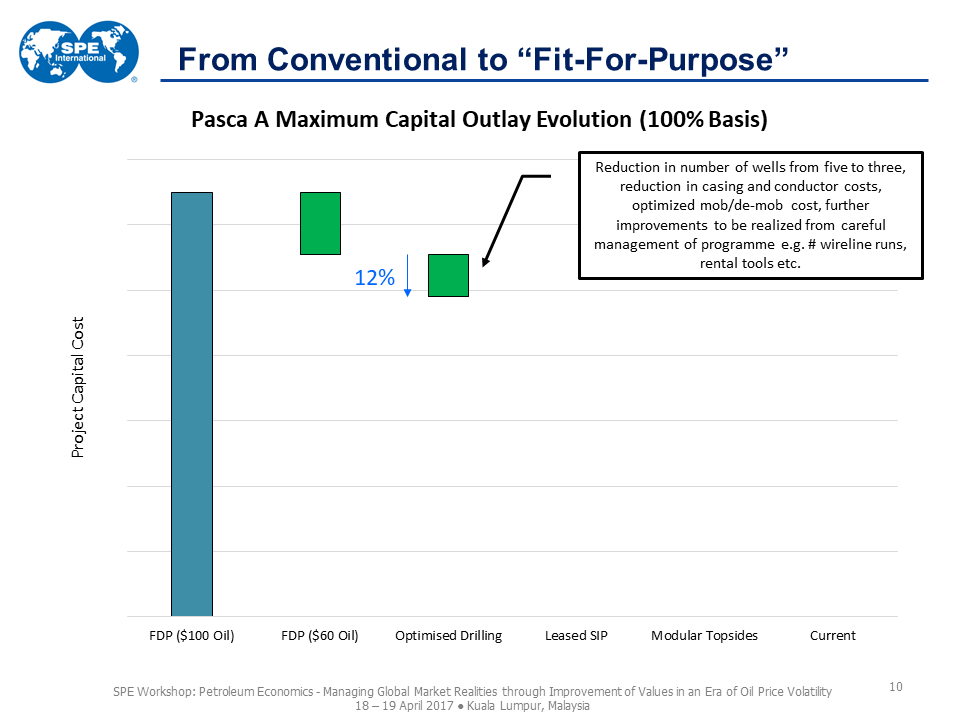

The next component concerns an optimisation of the drilling programme. Principally this is a reduction in the number of wells required, which is reduced from the original programme of five down to three. There are some other minor cost optimisations related to the formation evaluation programme etc., but the main saving is driven by a critical examination of how many wells are really needed.

Source: Twinza Oil

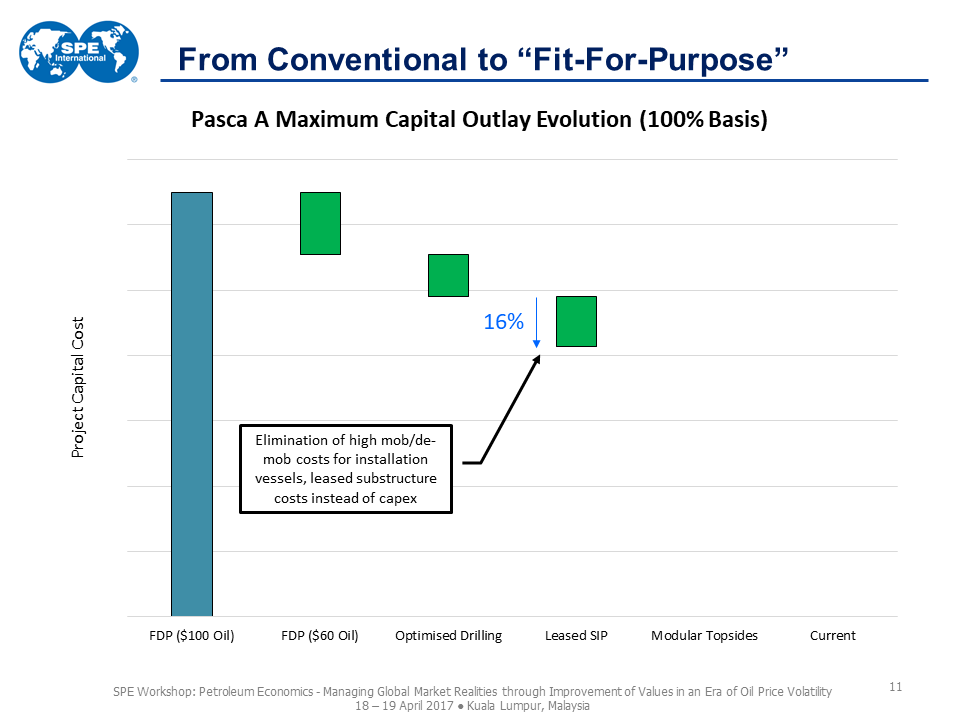

I mentioned earlier that one problem with the former fixed platform concept was the high mob/de-mob costs for installation vessels. Getting rid of those leads to a notable saving in the cost estimate. In addition, the jack-up platform concept opens up the possibility of leasing the substructure, rather than purchase. Some capex is still required, but the transfer of some capex into opex (through lease costs) greatly changes the up front capex profile for the project, and helps to improve the economic viability of the project.

Source: Twinza Oil

There are a host of other benefits. Buying modular equipment and integrating that into a topsides process design, rather than integrating the equipment into a bespoke topsides structure saves some cost. Using a flat deck onto which modules can be placed, rather than building an integrated structural deck reduces the bulk steel cost (plate steel is cheaper than structural tubular steel). Finally, eliminating unnecessary standards in the design leads to a reduction in cost. In isolation, each cost saving is small. Taken together the “fit for purpose” approach yields a saving of 65%. This is a reduction in cost of more than half.

Source: Twinza Oil

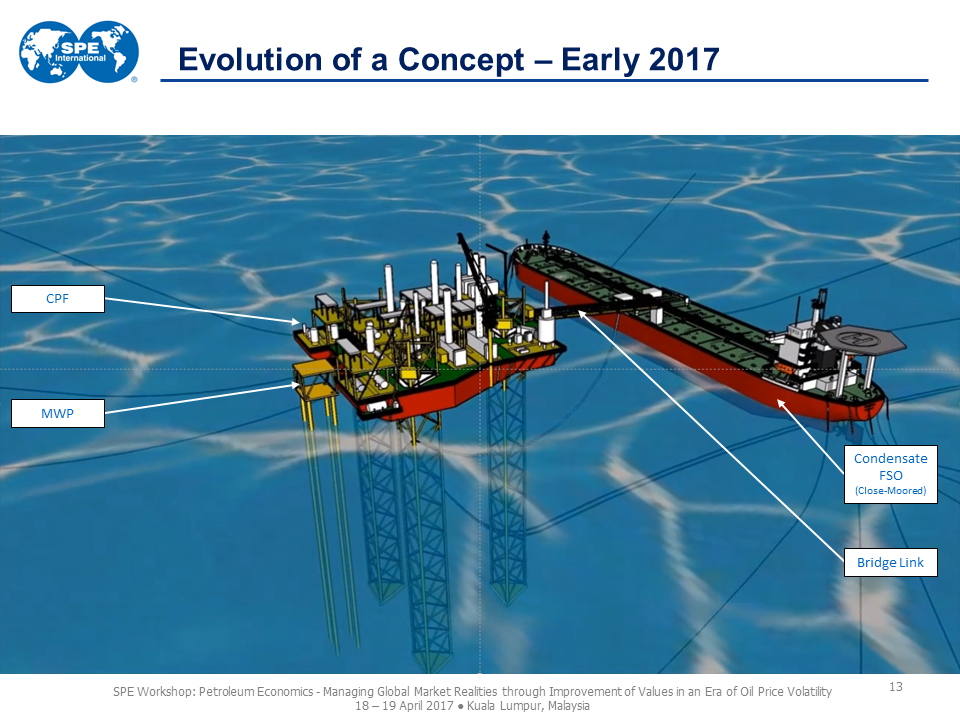

How does our concept look now? Figure 13 shows an updated 3D model of the concept. In place of a fixed platform structure with a nearby FSO, we now have a minimal wellhead platform that is braced to a jack-up alongside a spread-moored FSO with a walk-to-work gangway access. Quite a change in concept but a very cost effective one. I would note that this concept is unusual and is not the first idea that comes to mind. Instead it is the product of a systematic and critical assessment of what is really needed. The most important consideration is not how it looks, it is that it fulfils all its functional requirements. Do you really need to pay more just for something that is more conventional?

Source: Twinza Oil

Following the changes to the Pasca A concept, the project has managed to remain economically viable even in the current lower oil price environment. The breakeven for the project now approaches $20/bbl. If the oil price continues to fall we’ll need to look more critically at our concept, but for now we are comfortable with the approach proposed. For Twinza, taking a “fit for purpose” approach has paid off.

There was no single silver bullet that solved all the problems. It required a wholesale change in approach to the project and the concept, where all parts of the concept are challenged. Twinza believes that this outcome was only possible because it allowed the project team to adopt such an attitude. For Twinza this was an easy decision. If the project team were not given free reign to change the development concept, then the company would no longer have a viable project. In a larger organisation, there will often be resistance to taking a different approach. Yet as I observed earlier, I have seen large companies with project teams at both ends of the spectrum when it comes to integration and a proactive team approach, so I know it’s possible.

In the current oil price environment a more disciplined approach to the project’s development concept is needed. Simply continuing to churn out the same approach that worked during a high oil price environment won’t cut it any more. It will lead to higher development cost estimates, and potentially viable projects will remain unsanctioned.