As a hobbyist programmer, I’m keen to spark an interest in computers and programming in the next generation. There is a misconception that kids these days will be able to figure it all out by themselves and that tech is second nature to them. Wrong. Learning to use technology is the current generation’s forte, yet creating that same technology is just plain bewildering to them. After all, why bother why you can just download a hack that someone else wrote?

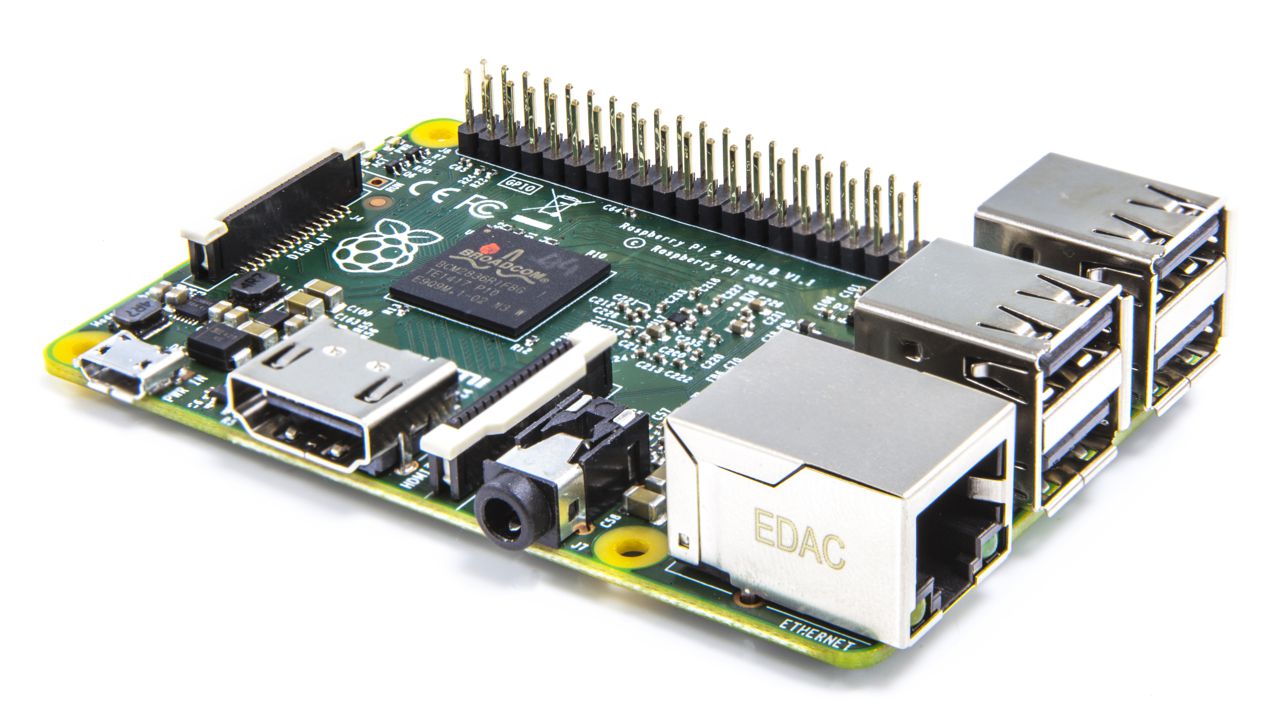

With the Raspberry Pi computer (or ‘RPi’ as it is often referred to in shorthand), and the Python programming language, a very cheap and accessible route for experimentation with computer programming is now available. This blog post attempts to explain the first steps that might be taken, but first a little background on what exactly the RPi is.

About the Raspberry Pi

It is a small, low powered, cheap computer about the size of a credit card. The model B has about the same processing power as a Pentium II from the late 1990s (around the introduction of Windows 95 if you remember that) but can do a whole lot more. It was specifically designed to make computing and programming accessible for those that want to learn. Hooking up the RPi to interact with the physical world (such as responding to sensors and triggering responses) is surprisingly easy. There is a massive community of enthusiasts who have embraced the RPi and done all sorts of things with it.

Why bother with such a low powered computer?

The creator of the RPi was a Director of Studies in Computer Science at Cambridge University, and had noticed a decline in the capability of students applying for the undergrad course since the late 1990s when most undergrads could do the equivalent of getting their hands dirty in the computing world, to 2005 when there were applicants that might have done some web page editing, and used some software, but had pretty much no idea about the basics concerning how computers actually worked. In less than a generation we’ve lost the ability to teach kids how to use computers.

The problem is that over time computers have become ‘easier’ to use. The innards are hidden away, and these days with mobile phones now having more computing power than mainframes of just a few decades ago, the computer is more of an appliance than a general purpose computation engine. When I was a kid there was the BBC Microcomputer. Using the BASIC programming language, you could do all sorts of things from robotics, music composition to the (even-then) ubiquitous games. When you turned a computer on you were faced with a command prompt and little else. Naturally you had little choice but to learn how to use it if you wanted to get anything done.

Our school had a wonderful policy at the time. Games were banned unless you had written them yourself. You might as well have dangled lollies in front of us. We needed no encouragement, and the computers of the era were simple enough to use for experimenting with programming and robotics. It didn’t matter if they games we wrote were not as good as the commercially available games – they were our games.

When my eldest child was much younger I tried to re-create this scenario, and told him that he was only allowed to play games with Daddy’s permission until he was 16 years old or if he had written them himself. As an aside, this backfired a bit when he was little and told a friend’s mum that, “Daddy says I can play with myself when I’m 16”… but I digress.

He was interested at first, and wanted to know how to write a game. I got him to write out and explain a game, and its rules, then we could try to code it. At this point I hit the main obstacle. The development tools today are very sophisticated, and in many ways it is much easier to write than it used to be. But the entry barrier is now much higher. We played around with Unity and for sure this is a great game creation programming environment that is free. However to make something basic in it you need to understand how to create 3D objects, how to code in C# language etc. I could cope with this, but soon enough my son lost interest. It was just too much all at once.

It is very much my view that one of the reasons for the RPi’s accidental success is that it replicates this learning environment from the original BBC Microcomputer days. One where curiosity is not just possible, but greatly rewarded. If we give an RPi to a child, it is their own computer. One that they will come to learn and understand every aspect of. They are no longer ‘borrowing’ a computer from mum or dad, or asking if they can play on their iPad or similar. With a low entry barrier, they should be able to get results straight away, not hours or days later (if ever).

Finding code snippets for games

So, assuming you’re still interested in programming something, you might be wondering where the best place to start might be?

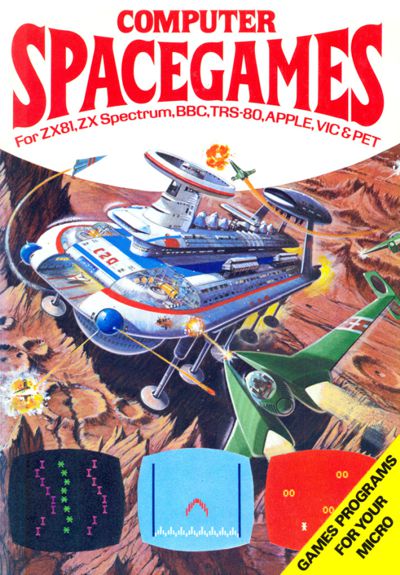

Call me biased, but it’s possible to go back to where I started. Usborne published a series of books in the 1980s that contained small computer programs that you could type into your computer and then play. Sure they were simple, but the satisfaction of getting it to work was brilliant. Usborne has made several of these books freely downloadable as PDF files now, which means the joys hidden within these pages are available once more to kids. The only problem is that the original code was written in BASIC for computers of that era: ZX81, BBC Micro, Vic 20 etc.

Fortunately the code is relatively simple, so it’s not too hard to port it to Python.

Let’s start with the first game I wrote from the book “Computer Spacegames”. I think I got this for Christmas in the early 1980s, and it was an absolute hit.

Writing a game in Python on the RPi

The first thing we’ll need to do is open up the Python environment which is known as IDLE. This is achieved as follows:

- Go to the RPi menu and navigate to Programming/Python 3 (IDLE)

- In the Python Shell open a new blank file that we can type our program into by navigating to File/New File

- Type the program below into the new window that opened up

- Save the program using File/Save (I saved mine as starship.py in /home/pi/Documents directory)

- Run the program using Run/Run Module or F5; the program should start running in the Python shell previously opened

Ported Starship Takeoff program in Python

The first program in the book is called ‘Starship Takeoff’, and it’s a good place to start. The game itself is incredibly simple, although the graphics and description in the book go a long way to boosting the overall immersion factor! The book explains all the lines of code, and I’ve similarly commented the Python code below (all lines starting with ‘#’ are comments and will not execute when the program is run).

The idea of the game is to guess a random number within 10 goes. The game will tell you if you are too high or too low. The game includes the following basic concepts:

- Basic mathematics and manipulating numbers in a program using variables

- Displaying output on the computer

- Requesting user input and using the result

- Basic logic and loops

For optimum mileage, this is best typed by hand. Inevitably there will be mistakes when first typing in programs by hand, and learning to find and debug those mistakes is a valuable step along the path to becoming a programmer.

import random

print("STARSHIP TAKE-OFF")

# Computer selects two numbers -- one between 1 and 20 to be put in 'g',

# the other between 1 and 40 to be put in 'w'.

g = random.randint(1, 20)

w = random.randint(1, 40)

# Multiplies the number in 'g' by number in 'w'. Puts result in 'r'.

r = g * w

# Prints "Gravity" and number in 'g'

print("Gravity = ", g)

# Function that runs if correct number is guessed.

def win():

print("Good take-off")

# This begins a loop which tells the computer to repeat the next section 10 times

# to give you 10 goes.

for c in range(10):

# Asks you for a number and stores result in 'f'

f = int(input("Type in force: "))

# Compare number in 'f' with number in 'r' and prints appropriate message.

if f > r:

print("Too high")

if f < r:

print("Too low")

if f == r:

win()

break

if c < 9:

print("Try again...")

print("You have ", 9 - c, " goes remaining")

else:

# Prints after 10 unsuccessful goes

print("\n")

print("You failed")

print("The aliens got you")

Once you’ve entered the program and have it working, there are some additional challenges you might like to try, a few of which are listed in the original book.

As an additional challenge you might consider the following:

- How many possible numbers are there in each game?

- What is the best strategy to guess the number in the least number of tries?

- Is it possible to always win the game?