There are several different topic areas that fall under the Management Technical Section (MTS) of the SPE. One of these is the macro-view concerning the future of oil and energy. This topic was chosen as the first for a new format “Think Tank” discussion session that the MTS is hoping to hold each quarter. The future of oil and energy is a very topical subject given the increased attention that is being directed towards the climate of our planet. Our industry, rightly or wrongly, is the subject of much attention and blame. Nonetheless the world still has a demand for petroleum products, and the big question is how much and how fast will this change as consumers transition to different sources of energy? Will the oil industry remain relevant and what role could the industry play in the future energy mix?

When I first put the slides together, I reached a conclusion that it was clear there would be a future for the oil and gas industry. This is not to say that renewables or other forms of energy won’t have a place either – because all energy sources will have a role to play. Yet when I prepared the slides, I wasn’t sure if this message would resonate with the audience or not. The winds seem to be blowing in a direction where endorsing the oil industry is taboo. However, just a few weeks ago, voices more prominent than my own have started to push back against a narrative that predicts the decline of the oil industry, and this garnered the attention of the mainstream media who relished the public fight between OPEC and the International Energy Agency. So it was with less trepidation than might have been that I started the discussion, knowing that perhaps I wasn’t going out on a limb on my own with this viewpoint.

The aim of the Think Tank virtual discussion was to be structured similar to the Advanced Technology Workshops that SPE runs. Rather than presenting a passive webinar, the goal was to briefly present a short series of highlight slides to prompt and encourage discussion. Everyone was then invited to participate. The discussion was also recorded so that a library of past discussion topics can be built up that may be of value in the future.

This blog post contains the presentation slides that I created to help encourage discussion, and the commentary for each slide which helps to explain the basis for that discussion. An important consideration I flagged at the start of the discussion was that I hoped to separate this topic from any discussion about “climate change”. Whilst I acknowledge that there exists a spectrum of views concerning the importance of this subject as a driver for the energy transition and net-zero goals, it is in itself a different topic. So, for the purposes of this discussion, I established the ground rules which were to accept that our sources of energy have always evolved and will continue to evolve, and the objective here was to discuss what that continued evolution could mean for the petroleum industry.

Discussion Slides

This section presents my slides and the notes for each slide. It should be fairly self-explanatory. As you consider the slides and the commentary, have a think about what your own views are. There are no right or wrong answers.

Source: Peter Kirkham, EI Statistical Review of World Energy

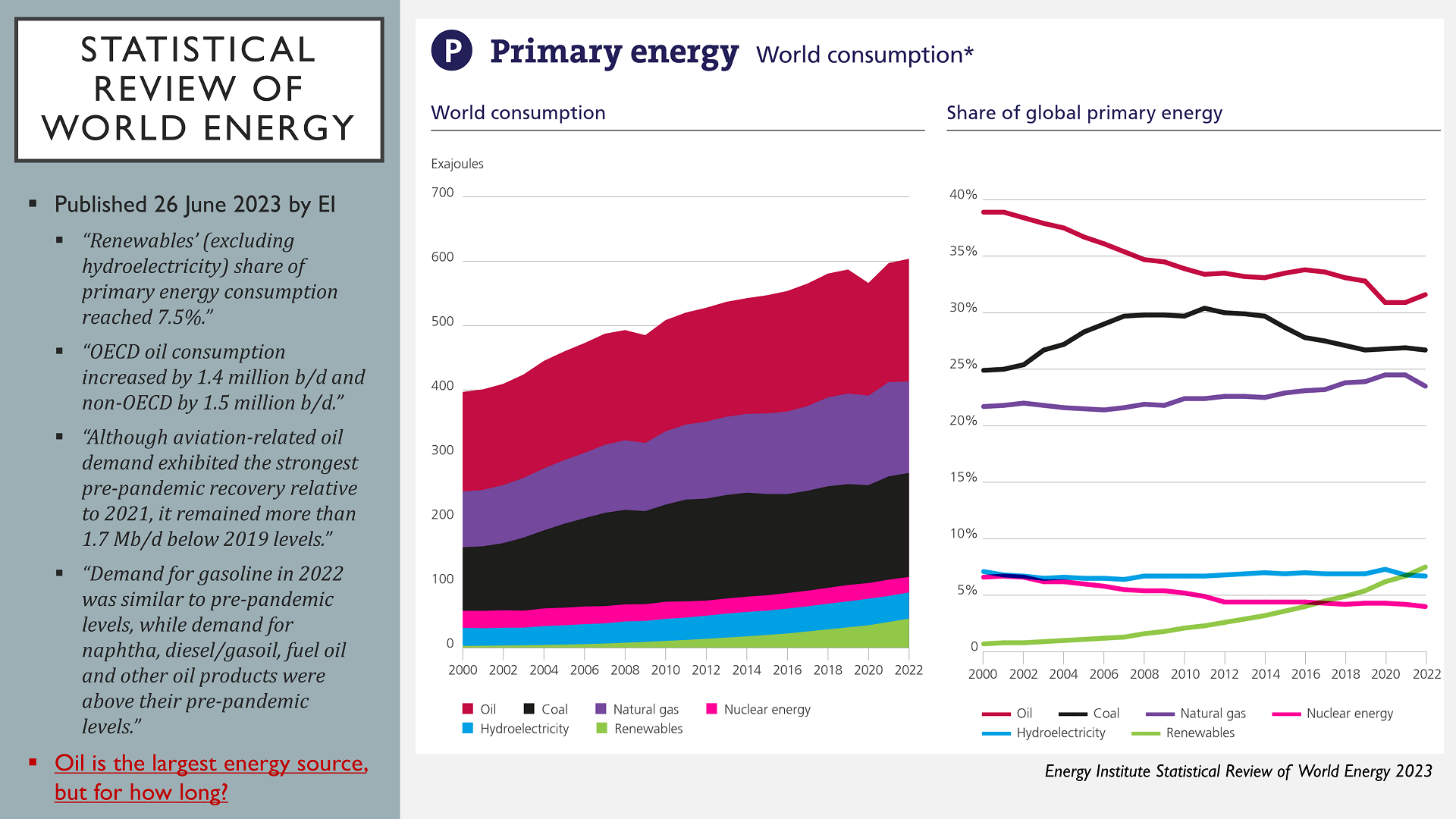

Let’s set the scene first. I’m sure many of us have heard of the Statistical Review of World Energy. This annual publication, for many years under the stewardship of the oil company BP, has recently come under the responsibility of the Energy Institute and the latest edition was published in June 2023. The review provides a valuable insight into the current state of energy usage in the world. The data are freely downloadable and can be manipulated and interrogated to garner further insights – something I will do in the next few slides to help reveal some subtleties that are not readily apparent when just looking at the historical consumption figures.

So, what does energy consumption look like today? I’ve selected a couple of charts and some quotes from the report which I hope give a good overall flavour. Total energy consumption continues to rise. A couple of minor blips are apparent in 2009 and 2020 as a result of a global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic respectively. Neither of these events have led to any long-term change in the trajectory of overall energy demand. Aside from aviation fuel, demand for most refined petroleum products is at or higher than their pre-pandemic levels. What is apparent is that the share of renewable energy contribution to the overall mix continues to grow. Currently this stands at 7.5%. Together with other low-carbon sources such as nuclear and hydro, these now account for 18% of energy supply. There can be little doubt that an energy transition is underway from fossil fuels to low-carbon alternatives.

Question to audience: Despite these changes, oil remains the largest source of energy, supplying 32% of primary energy demand, although the proportion of energy supply met by oil is on a downwards trend. Will this state of affairs last for much longer?

Source: Peter Kirkham, EI Statistical Review of World Energy, EIA, MMS/BOEMRE, CAPP, DOGGR, Published Company Data

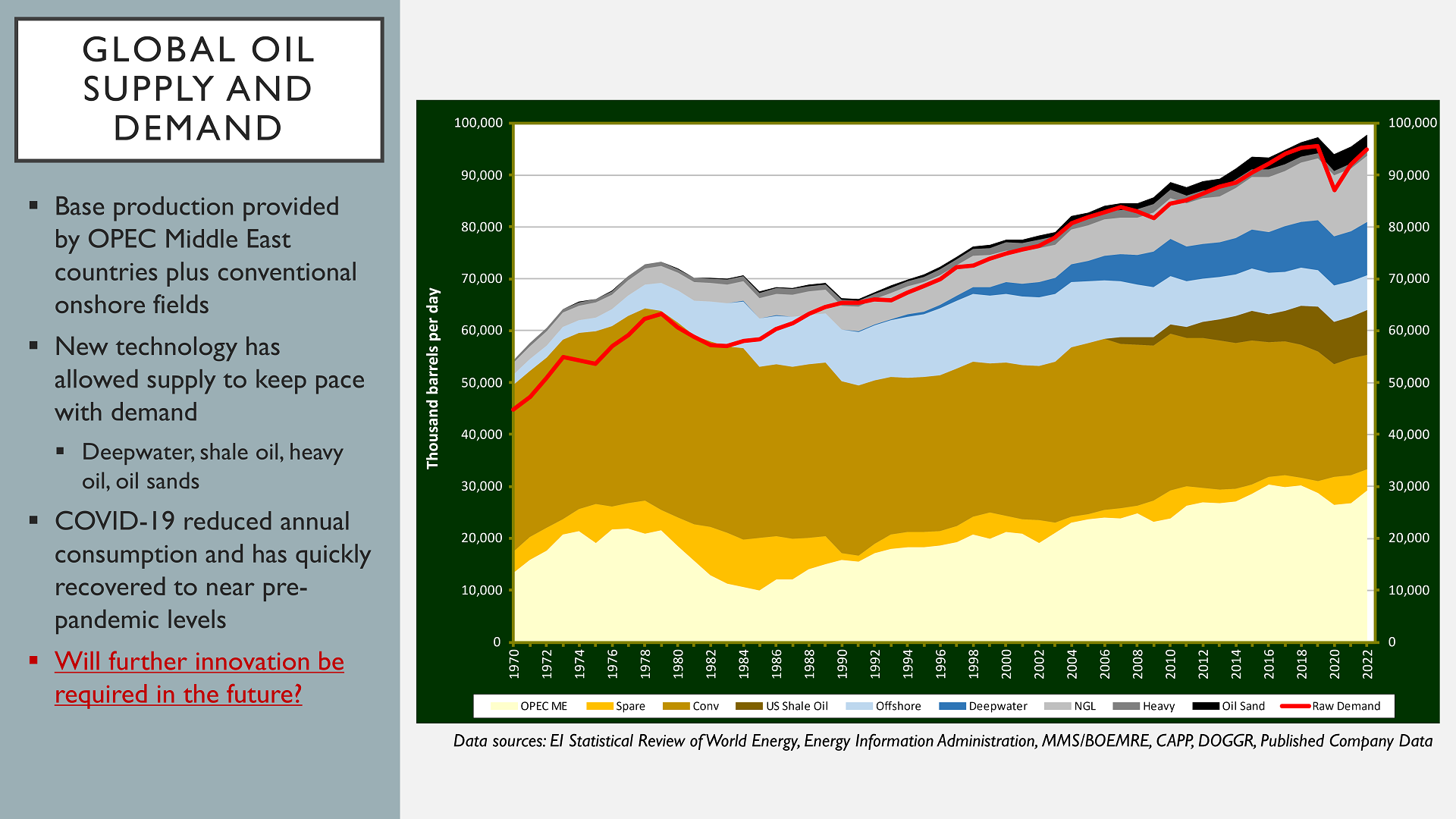

Let’s look a little closer at oil as an energy source. The Statistical Review breaks down the supply of oil by different countries and regions. Using additional information sources, it is possible to further break down the supply of oil into different types of production, as shown here. What this shows is how oil industry has introduced new technologies to move from a predominantly onshore nature in the early 1970s to a mix today that includes shale oil, offshore production (both shallow and deepwater), heavy oil and tar sands. The growth of natural gas production, and natural gas liquids (condensate) is also very apparent from this graph.

The reduction in oil demand from 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic is an interesting data point. I’m sure we all have our own personal experiences of lockdowns that were implemented variously across the globe; a consequence of which was a significant reduction in oil used for transportation fuels. Given that the lockdowns in many countries simultaneously contributed to a reduction in the volume of vehicle traffic, airline travel and even shipping, the COVID-19 pandemic period could be considered a proxy experiment that provides some insight into the significance of substituting a large proportion of internal combustion engines for electric vehicles. It is interesting to note that whilst there was an observable drop in oil demand over this period, it was less than a 10% reduction in oil demand, and annual oil consumption has already recovered to near pre-pandemic levels.

Question to audience: With that in mind, will our industry need further innovation in the future to continue delivering increases in the daily supply of oil, or is this, as some pundits have speculated, the peak of oil production that will never be seen again? In a 2021 report the IEA suggested that the drop in demand as a result of COVID might represent a “new normal” and in their report on the pathway to net-zero, also published that year, they state (and I quote), “no new oil and natural gas fields are needed in the net zero pathway”.

Source: Peter Kirkham

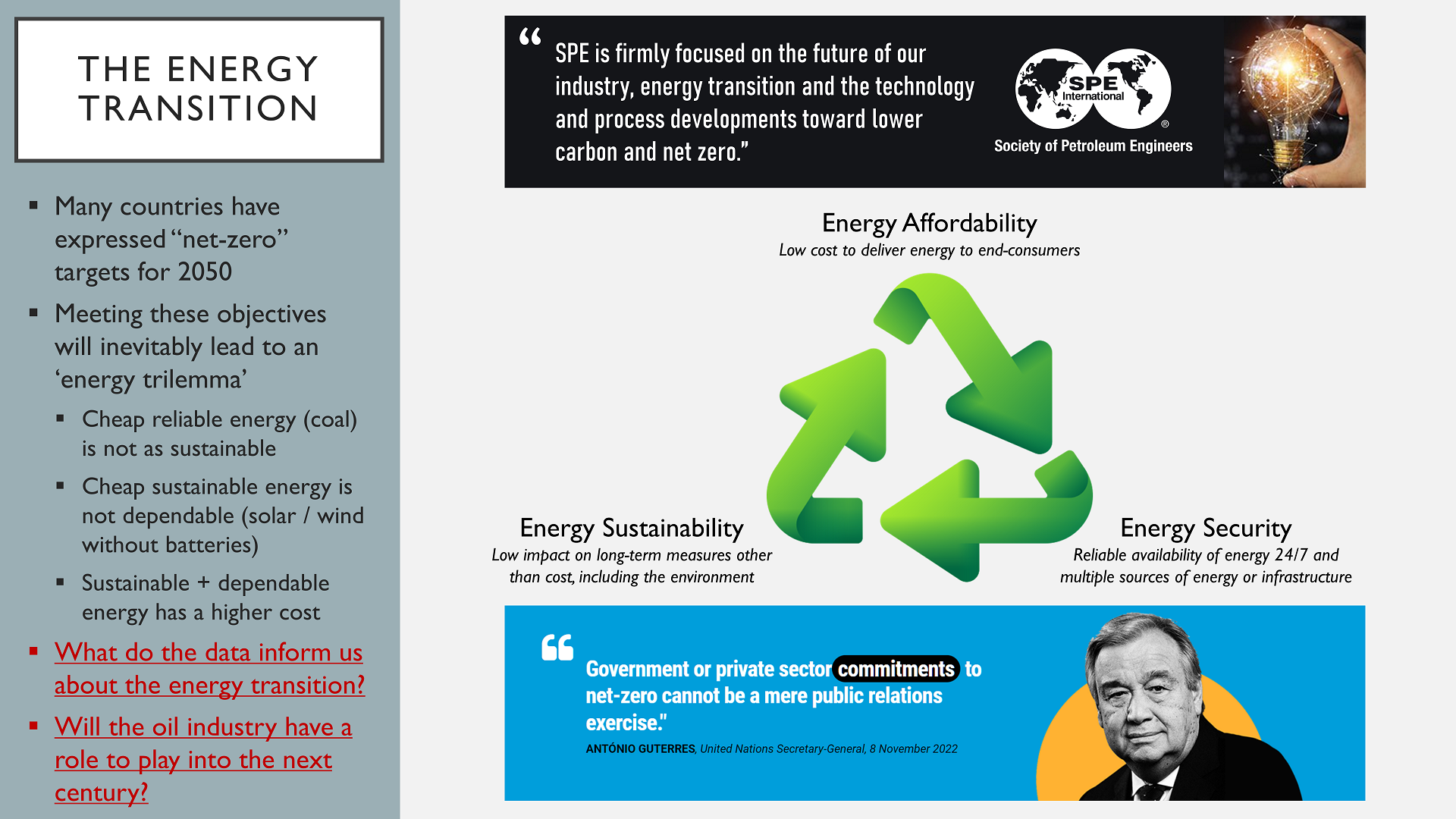

I’ve mentioned the “energy transition” and “net-zero” a few times. The objective is to reduce the net mass of carbon dioxide produced when using energy, either through capturing or offsetting the carbon dioxide produced, or simply through not using energy, or switching to energy sources that do not produce carbon dioxide. It is a simple principle and gets a lot of traction with society in general. If anything, governments are still criticised for pledges to “net-zero by 2050” not being fast enough. However, I did say at the start that we wouldn’t debate “climate change”, so let’s put that to one side. The issue we face as engineers is that whilst “net-zero” is easy to say, it’s quite another thing to implement on the scale that is talked about.

Fortunately, engineers tend to be practical folk that relish a challenge. I have no doubt that collectively we will be able to deliver what is needed. The problem is, as the saying goes, “you can’t please all the people all of the time”. There are trade-offs that will need to be considered, and this can be understood readily as an “energy trilemma”. Basically, in an ideal world where there are three qualities that we really want, we instead get to pick two that we prefer and accept that the third will be less than ideal. With energy we consider affordability, sustainability and security. Ideally all energy would be cheap, clean and reliable. Except it isn’t. Cheap reliable energy such as coal, the backbone of the energy infrastructure we have today, is no longer considered environmentally sustainable. Cheap sustainable energy can be done; in Australia where I live the adoption of rooftop solar has been astounding because it is economically attractive in comparison to only buying electricity from the grid. However, it only generates when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing. Fortunately, solutions exist, and to deliver 24/7 electricity would require further investment in batteries (at a higher cost) or for locations without reliable sun and wind it would be necessary to generate at a distant location and deliver the power via cable (also at a higher cost). So, as I say – affordability, sustainability and security. Pick two…

Question to audience: How does oil and gas fit into this energy trilemma? Is there a continued role for our industry into the next century?

Source: Peter Kirkham, UN Population Division

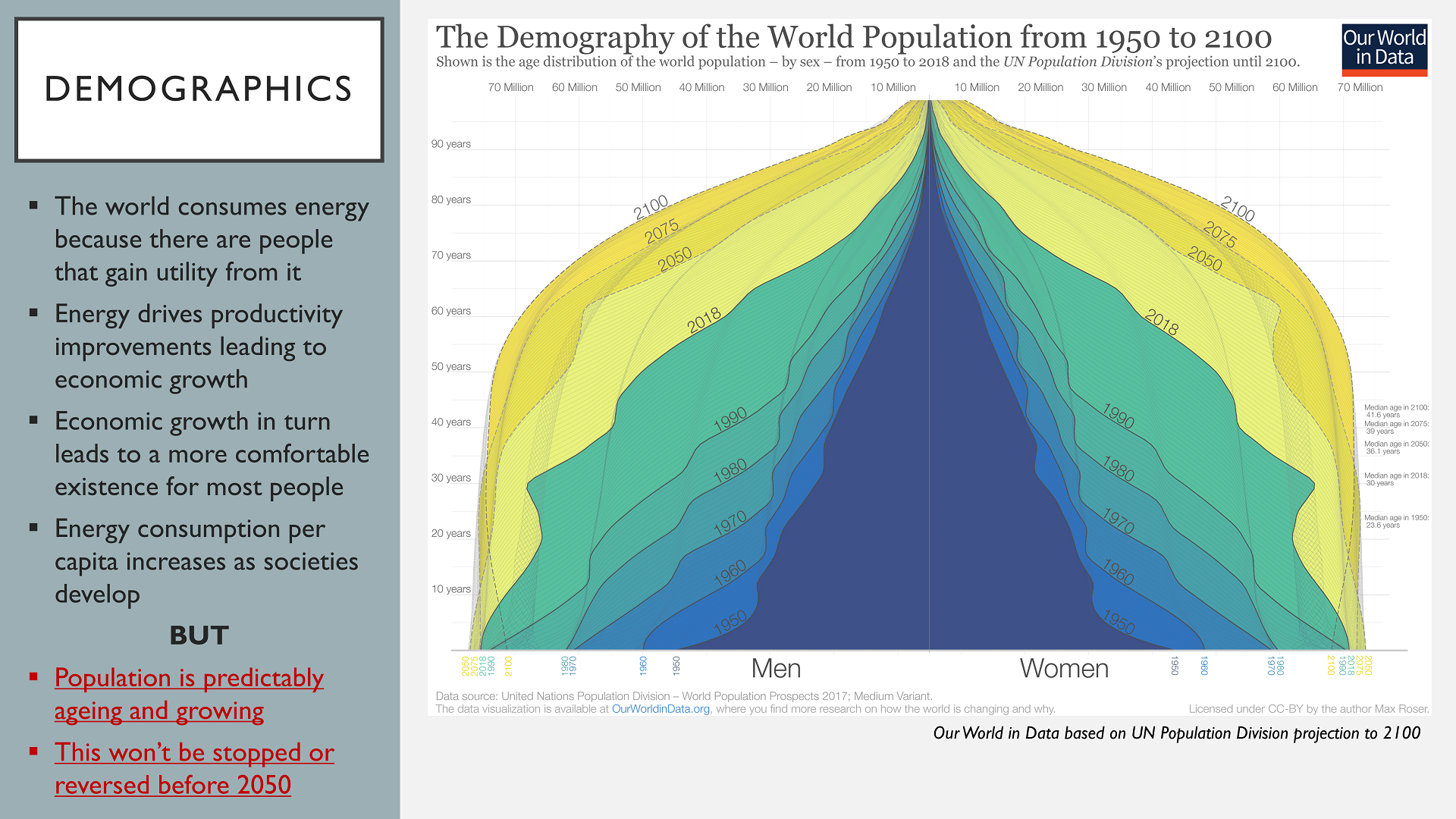

Before we can consider the role of the oil industry, there is one additional aspect I want to throw into the mix for consideration. It’s an issue that I find isn’t often talked about. Why do we even use energy in the first place?

Let’s face it, energy is a good thing. It improves the comfort and well-being of people within a society. Less developed economies want more of it, and when they get it, it helps drive development of that economy. Historically, as economies have advanced, the energy consumption per capita has increased. That is a fact that is unlikely to change in the near future.

Demographics is also a reality that cannot be ignored. Improvements in healthcare and quality of life have meant that infant mortality has decreased. Babies born today have a longer life expectancy and the proportion of elderly people (>65 years old) in the world is increasing. These trends are fairly predictable, and whilst there is some uncertainty around the rates of growth, it is very likely that population growth won’t be stopped or reversed before the target net-zero date of 2050.

What this means is that we can’t look at the energy transition with reference to where we are today. We need to look at trends with respect to energy consumption per capita, and population growth.

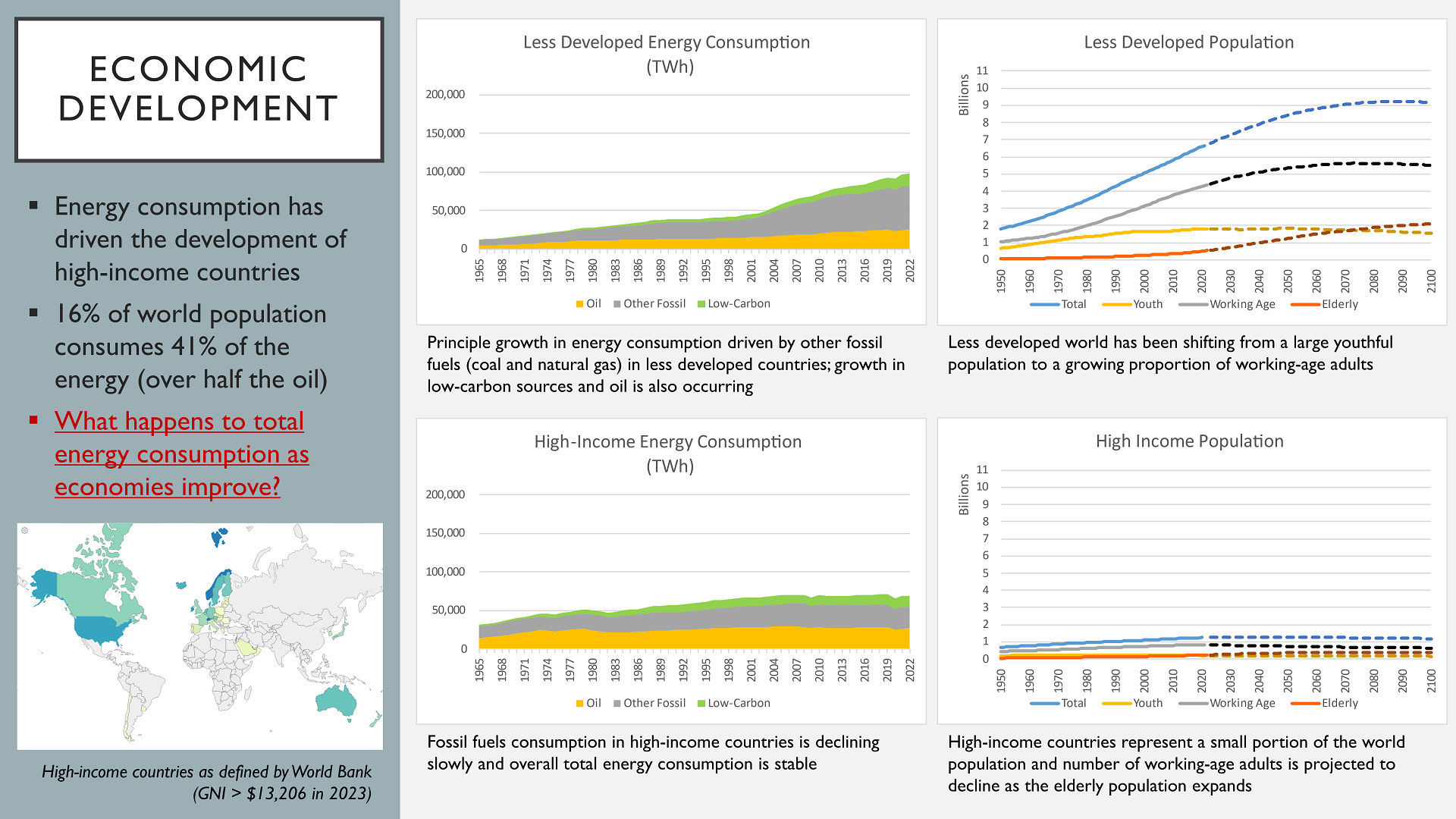

Source: Peter Kirkham, World Bank

We must also recognise that energy consumption is not equal all around the globe. For convenience, I’ve illustrated this by splitting the world into two: high-income countries (as defined by the World Bank – you can see these on the map) and the less developed countries.

Historically the high-income countries consumed most of the world’s energy. Arguably it is the very result of this energy consumption that has led to them being ‘high-income’ countries. Yet the high-income countries only represent a small proportion of the world’s population. The energy consumption in this bloc of countries could be considered relatively stable and their population is ageing and projected to decline.

Of course the populations of many other less developed countries would also like to share in these benefits, and within the last decade the energy consumption for these less developed countries has surpassed that of the high-income countries. In some respects, whilst it matters what this bloc does in response to the energy transition, it could be argued that it is of secondary importance when compared to the less developed bloc of countries. Here the working-age population is forecast to increase, and on an energy per-capita basis, it would be reasonable to expect that this part of the world will increase their consumption of energy.

Question to audience: There are a variety of factors to consider in the energy transition. The energy trilemma underpins our choices of energy supply, and global demographics and economic growth drive the demand for energy. What does the combination of these factors mean for total energy consumption?

Source: Peter Kirkham

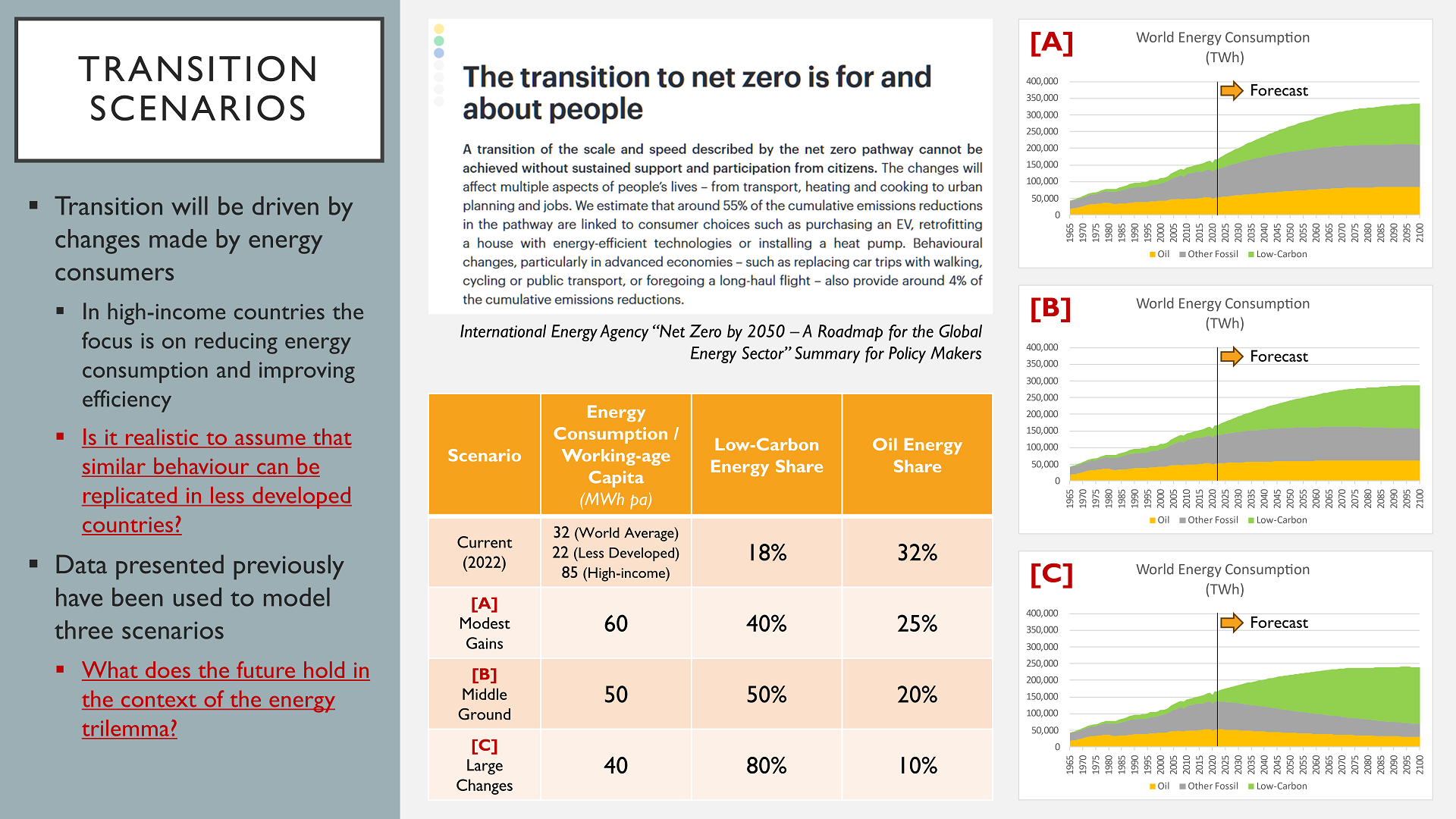

In this last slide I present some possible outcomes. I should stress that at this point I’m moving away from the data, and extrapolating, and that these are my personal projections. They are not intended to be definitive, nor accurate. The intent is to provide an informed framework for further discussion.

The energy transition will be shaped by changes in the behaviour of people. How much energy they consume, and how much they are prepared to pay for that energy. On one side of the equation, the high-income part of the world can be expected to reduce their consumption through gains in energy efficiency and conservation efforts, such as the use of electric vehicles, heat pumps, cycling or public transport instead of driving (as noted by the IEA’s roadmap to net-zero by 2050). On the other side, improvements to economies around the world will lead to an increase in energy consumption that will start to approach that of the high-income countries. At present, the average energy consumption per working-age capita is 22 MWh pa in less developed countries and 85 MWh pa in high-income countries. As an assumption, we might assume that energy consumption converges towards a value in the middle, but above the current world average.

Question to audience: Such a convergence assumes that less developed countries immediately benefit from the energy efficiency improvements delivered by technology advancements. Is that a reasonable expectation?

On the supply side, we can project that the share of low-carbon energy sources increases and that of oil decreases. A possible range of outcomes, from modest through to large changes is shown in the table, with scenario [A] representing the least change and scenario [C] the most. Note that even in scenario [A] there is a change taking place – this is not a “do nothing business as usual scenario”.

By combining these macro-economic parameters, it is relatively trivial to project the energy consumption into the future for a given set of assumptions. What is interesting is that in all scenarios, there is still consumption of fossil fuels and oil in the future. In these scenarios, there is a need for new oil and gas fields to be developed. There is a future for the oil and gas industry, it just won’t be as dominant as it is today. I believe that is OK.

Question to audience: These three scenarios are just three that I’ve put together in the context of the macro-economic drivers of energy demand. But are they credible? Does the energy trilemma instead show that the true cost of fossil fuels is much higher than the financial cost alone, which would lead to a near-phasing out of all fossil fuels within our lifetimes? Or perhaps the modest changes indicated here appear too far-fetched and unrealistic? To come back to the question stated at the very start: Will the oil industry remain relevant and what role could the industry play in the future energy mix?

Highlights from the Discussion

The great thing about a discussion like this is that although I’d prepared the slides myself, and had a particular set of thoughts in mind when I prepared them, they prompt different thoughts from other people which enriches the discussion for all involved.

The first slide on historical energy sources really helped to set the scene. As we looked at the data, others in the discussion noted some aspects that I hadn’t seen before:

- A comment was made that for many years (decades) BP had compiled these figures. Whilst I had always been of the view that this was a service for which the world should be thankful for BP, given that it was shared for free, apparently not everyone shared this viewpoint. The view was that BP, being an oil company themselves, were somehow manipulating the data to paint a biased view of the oil industry. This year marks the first year that the responsibility has been transferred over to the Energy Institute.

- Coal is still very significant. Whilst oil provides the largest share of energy, and much fanfare is noted around how its share of world energy markets is declining, coal’s appears to have stayed relatively strong in second place and is not declining.

- In 2022 natural gas contribution to world energy decreased, despite years of slow and steady growth. This was noted as unusual because gas is frequently promoted as a cleaner alternative to other fossil fuels. I noted that this was probably due to high prices in 2022 where the cost of LNG had increased dramatically. A subsequent check on historical LNG prices in 2022 confirms that this could be the reason why natural gas demand decreased in 2022.

- The two ‘notches’ in energy demand in 2009 and 2020 are interesting. The most recent one we are familiar with, related to COVID-19 lockdowns. The previous one was the financial crisis which led a drop in economic activity. However, these events which both seemed like a big deal at the time when they occurred, don’t appear to have had much affect on the inexorable growth in energy consumption.

Having set the scene I moved onto the second slide and explained that I was moving away from a pure presentation of the statistical review data itself, and now using that data (or more accurately manipulating it by combining it with other public data sources) to deliver a more nuanced view. This was well received. Everyone wanted to know where I got the data from, and I explained that I had gone through the regional/country data from the statistical review, and then split that into different sources. For some countries you know that they are almost all onshore or offshore, and others publish their own data on the sources of oil production. What this means is that you can start to piece together a picture of how oil supply has evolved over time. It takes a few days of effort (at least the first time you do it), but otherwise all the data is freely available and published in the public domain. I don’t often see historical global supply broken down like this. I guess that’s either because no-one else, apart from myself, is interested in breaking it down in this fashion, or because the data is, for some reason, not easily available pre-packaged and neatly curated off-the-shelf. Maybe it’s both?

Personally, I find that the growth of shale oil in the US is staggering. As one who had initially thought that the high well decline rates would lead to a production treadmill that just couldn’t be sustained, I have to admit that I was wrong. You can’t argue with the data. Other participants in the discussion found it really interesting to see how the growth in offshore production follows on from the establishment of the Offshore Technology Conference, and that deepwater growth in the 1990s also parallels the increased focus that received from SPE in that era.

In contrast, it was observed that heavy oil and oil sands, whilst often touted as having huge potential in places such as Venezuela, had not experienced the same level of growth. Certainly the energy needed to extract those resources means that they would require much higher prices to justify a large expansion in supply. That may be so, although I’ve got enough experience now to know it’s wiser to “never say never”.

Slides 3, 4 and 5, which set out facts about the energy trilemma, global demographics, and the contrast in energy consumption and projected population growth between more developed and less developed economies of the world, did not provoke as much discussion. Fortunately there was little disagreement with the data, as this was crucial for setting the scene on the last slide.

The discussion on the last slide was that the growth in energy demand and the continued need for oil was something that wasn’t often shown. One very interesting comment was that at the recent ATCE in Houston, people had started to use the phrases “energy addition” or “energy expansion” instead of “energy transition”. To me this makes a lot of sense. To meet growing demand for energy, it would make sense to build more energy sources that meet our current aspirations / societal expectations for sustainable energy. Whether that energy is sustainable and reliable, or sustainable and cheap remains to be seen (remember you can’t have all three in your cake and eat it too). Thus, a large portion of future growth in energy demand is likely to come from renewables. Yet against this backdrop there is still room for growth in oil production. Oil may not remain as the largest source of energy in the world, but that doesn’t mean it will go into decline. Much like how China is often maligned as being dependent on a growing coal industry, how many are also aware that there has been massive growth in renewable energy in that country? Again, it is not an either / or conservation. The future energy needs of this planet will be met from a variety of sources.

The final slide also sparked a discussion on carbon capture and storage technologies. That with growth in that particular technology, the balance of carbon-intensive to low-carbon sources would shift further towards the sustainable axis as it is possible to offset a portion of the carbon dioxide emissions through capture and sequestration. The concept of “artificial trees” was mentioned as a concept, albeit one that had been dismissed on the grounds that you couldn’t possible build millions and millions of artificial trees. The person contributing to the discussion merely noted that last year the world apparently manufactured 85 million new vehicles. That puts the dismissive comments into perspective. If we deny ourselves the imagination to consider how a solution could be implemented, then all we are doing is putting barriers in place towards its eventual acceptance. Good solutions will usually win through. Eventually.

Conclusions

Energy is fundamental to a comfortable life for societies in our world. As the world population continues to grow, and as economies continue to develop, the average energy consumption per capita will continue to increase. Perhaps we won’t ever reach a global average on a par with current energy consumption per capita in developed countries, but as energy efficiency is implemented there should be a convergence in energy consumption per capita between the developing economies and the developed economies.

Overall this means that energy consumption will inevitably continue to grow. Much of that future growth could be met by renewable sources, yet even in that scenario there is still likely to be growth in oil and gas demand. So to come back to the original question, given the trends in historical energy demand and the often touted energy transition, will there be a future for the oil and gas industry? I believe the answer is a resounding “of course”. The challenge for those in the industry, is how to deliver new field developments and sustain existing production, in an environment where society seems desperate to avoid being seen to finance or support the oil industry? Well that question will need to wait for another day.