A few days ago an email with highlights of the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) Oil and Gas Facilities journal arrived in my inbox. I was immediately captured by the lead article which was titled “Why Do E&P Projects Fail?”. Since this is a topic on which I was involved researching whilst at IPA, I was wondering if it was something that had been written by one of my former colleagues.

The Message Spreads

As it turns out the article was not written by one of my former colleagues, but by Stephen Whitfield, so I was very interested to see exactly what basis was used for drawing the conclusion. As I started reading the article, on the very first page I was astonished to see my own name.

A recent study of scheduling effectiveness reported that from 2003 to 2011, 54% of authorized E&P projects were planned with a schedule that was faster than similarly scaled projects within the industry (Nandurdikar and Kirkham 2012).

Wait a moment… Did I just get referenced in a journal? For me personally this was a big moment because I have have only had a grand total of one article published – the very same article that was referenced here. The article is “SPE 162878 The Economic Folly of Chasing Schedules in Oil Developments and the Unintended Consequences of Such Strategies by N. Nandurdikar and P.M. Kirkham, Independent Project Analysis.”. The article was written in 2012 in preparation for a research study to be presented later than year, more on which later in this article.

Whitfield’s article is a blend of the data-driven IPA mantra, together with other viewpoints. As an ex-IPA employee I don’t agree with the view that there is too much front-end loading on projects, but to be fair Whitfield doesn’t appear to support it either. To deliver a successful project you need to set it up correctly, and then control it effectively during execution. In other words you need planning and control. Control is worthless without planning, and even if you set a project up very well for execution, you can still throw it away during execution if you have poor control.

It’s great to see a slow but growing acceptance that the way the E&P industry currently pursues projects is not sustainable. The days when we could get away with mediocre results because increasing oil price would bail out the project are behind us. Nothing but excellence in project delivery is now acceptable.

The IPA Perspective

Of course I shouldn’t be surprised that IPA has also got something to say on the subject. Co-incidentally one of my former colleagues published a guest editorial in the October 2014 edition of the Journal of Petroleum Technology titled “Wanted: A New Type of Business Leader to Fix E&P Asset Developments”.

This editorial has a similar theme to the Whitfield article, but leads into a discussion on what the cause for project underperformance might be in the context of E&P portfolios. The editorial also draws on work that I had contributed to whilst I was at IPA, so given that two separate articles which have drawn on that work have just been published, it seems appropriate to describe the history of that work.

True Economic Impact Of Project Decisions

In 2012 Tom Mead (a research analyst at IPA) and I were tasked with looking at the effect that project decisions have on the NPV of projects. The background to the study was to disprove claims by a project that will remain nameless, that they had been a great success principally because they delivered a fast project on schedule. Given that this project had experienced problems during execution, this was a simply staggeringly claim. With the bullshit-o-meter going off the scale, we undertook a broad look at what drives NPV erosion in E&P projects. Our hypothesis was that the focus on schedule was misguided at best, and fatally flawed at worst.

Our approach was to use IPA’s database of E&P projects and compare the actual outcomes in terms of cost, schedule, reserves, production versus those that were promised at sanction. Since IPA didn’t have the commercial models for these projects, we built a several hundred economic models, two for each project. These models allowed us to compare the NPV promised at sanction against what that NPV would have looked like if the project team had a crystal ball and had instead used the actual outcomes. This was no trivial exercise. The results were presented at the Upstream Industry Benchmarking Consortium in 2012 and were very well received by the audience.

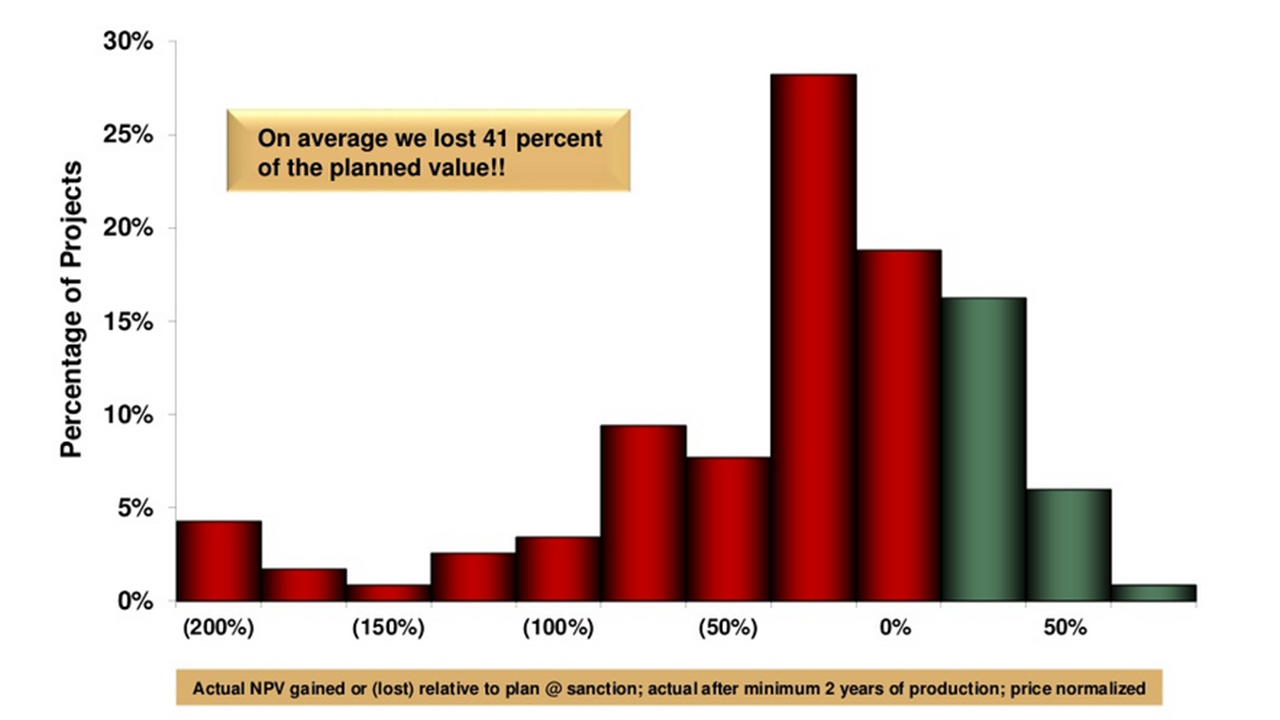

The material we presented at UIBC is confidential, so I cannot share it here. However IPA presented at the Offshore Technology Conference in 2014 and that presentation used elements of the research Tom and I did for UIBC 2012. A histogram showing the NPV gain and loss for the several hundred projects that we evaluated is shown in Figure 1. Note that this shows the gain or loss of NPV divided by the estimated project capex, not the original estimated NPV. We needed to do this because there were more than a few marginal projects which had low estimated NPV (the so-called ‘strategic’ developments) and their low NPV meant that their relative change in NPV was huge.

Source: Declining Terms of Trade: Why Only The Most Efficient Will Survive The Cost Price Squeeze, Neeraj Nandurdikar, Independent Project Analysis, OTC 2014

There are several points to note from this chart:

- More than 70 percent of projects actually lose NPV.

- The average change in NPV is a 41 percent loss.

- The distribution is heavily skewed to the downside.

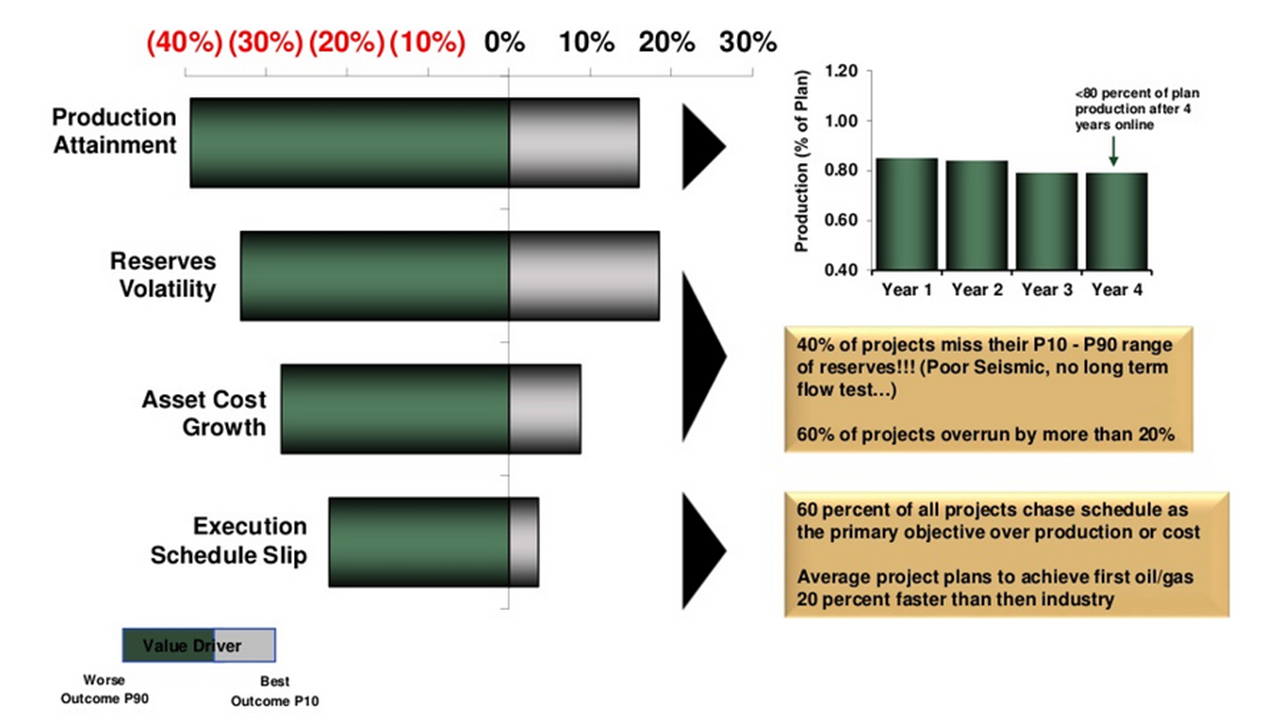

Why do so many projects lose value? Through statistical analysis of the data, we were able to then determine the main drivers of NPV gain or loss, in terms of changes in the various outcome metrics. The results were then presented as a tornado chart as shown in Figure 2. It should be noted that unlike classical sensitivity analyses which look at the effect of an arbitrary change in input variables on the outcome, this analysis was based on actual project results. In other words this is not a mere sensitivity test, it instead reveals the actual drivers of NPV loss in order of their importance.

Source: Declining Terms of Trade: Why Only The Most Efficient Will Survive The Cost Price Squeeze, Neeraj Nandurdikar, Independent Project Analysis, OTC 2014

The findings were not necessarily surprising, but they are definitely critical to understanding why projects fail:

- For every single asset outcome, the NPV loss is larger than the NPV gain. In other words, there is no area in which projects could claim to deliver good results – even schedule.

- Many projects will emphasise speed and the time to first hydrocarbons, and whilst faster schedule does indeed drive higher NPV, it is not the most important aspect to consider.

- Production is the biggest driver of NPV gain or loss, and ensuring production forecasts are achieved is thus critical to successful project delivery.

- On average projects only produce just over 80 percent of plan in their first year, and this does not improve in later years. It is a myth that projects will generally recover production once initial problems are remedied. If there are early problems, the data suggest that this is indicative of fundamental issues that will continue to limit production.

- As an industry we are woefully bad at accurately predicting cost and reserves. The P90 to P10 ranges that are estimated appear to be more like P70 to P10 ranges with the downside not adequately recognised. As for cost estimates at sanction being +/- 10 percent… what a joke.

- Is schedule the root of the problem? It’s not the only issue, but many projects set schedule as the most important goal and also set aggressive schedules. Given that fast schedule targets are correlated with lower production attainment (Nandurdikar and Kirkham), and production is the main driver of NPV loss, is it any wonder that E&P projects are failing when schedule is habitually set as the main priority?

Now the really interesting part about the research is what is not shown. Given the main findings that appear to show schedule as the culprit for poor results, Tom and I tried to show that there was a statistically significant relationship between projects that have aggressive schedules and large loss of NPV. The relationship never made it into the research study for the simple reason that it didn’t exist. Which was shocking at first, and there was a low point in our research efforts where we thought the whole study was a write-off. I think it was Tom that first realised we needed to group our schedule aggressive projects into two different classes. One where the goal was schedule to the detriment of all other aspects, and another where the focus was on preparing and planning the project well, with schedules that are faster than an industry benchmark as a side-effect.

In other words it is possible to deliver a fast project, but you won’t get there if that is the goal. Fast schedule is delivered by good planning and control of a project. On the other hand if fast schedule is the goal, then usually front-end planning is the first part to be cut out, and in doing so the project seals its own fate.

Addressing Project Failure

Having established and quantified the nature of E&P project failure, what solutions do I propose?

Well as I am now back on the owner side, the need to deliver project success has taken on more than an academic interest. As of today I don’t have any immediate solution. However I am working towards developing an asset evaluation tool that will help to highlight the importance of various decisions that might be taken during the planning phases of a project. In doing so I hope to be able to more ably demonstrate the true value of information, such that more informed decisions can be made.

The tool is ultimately being developed for my own use and I believe it will be an important contribution to my current work at Twinza. This is the best way to develop any tool in my opinion. Not as a product that might be sold, but as a solution to a problem that needs to be solved by the developer. Will it work, and will it be useful? This I don’t know, but I’m fairly sure that if it works then I’ll share the results in this blog and maybe even try to get them published one day.

As for Twinza, I assure you we are staying far away from being schedule-driven to meet an unrealistic first hydrocarbons date!