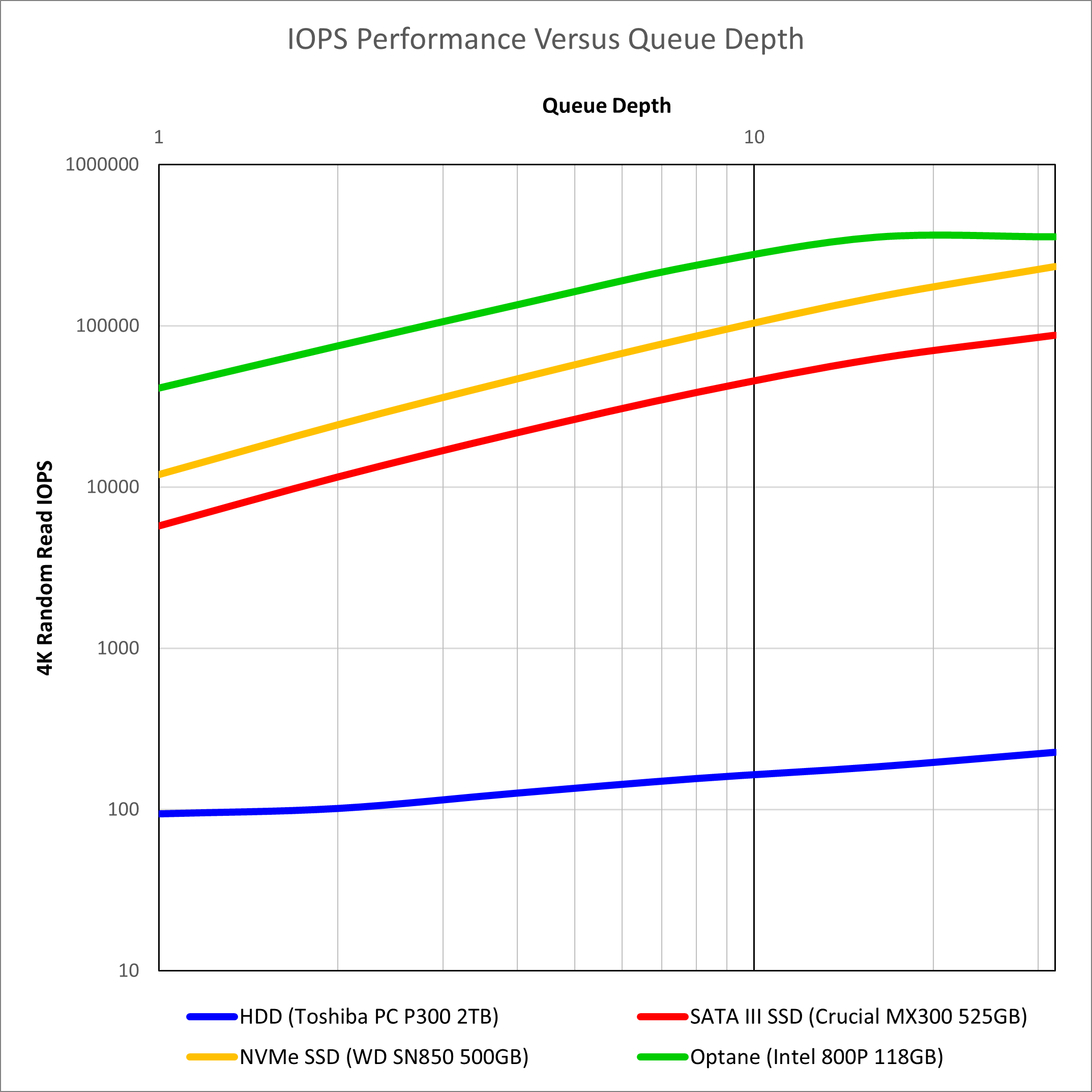

Previous analysis into the inefficiencies associated with reading SEG-Y seismic data led to the conclusion that a reorganised file structure using chunking combined with faster solid state drives would lead to faster average read times for inlines, crosslines and slices. A key finding was that the seek time, or latency associated with accessing the location of data within the file was critical. The new 3D XPoint non-volatile memory technology developed by Intel and Micron is a hardware solution aimed directly at solving this problem. The premise of Intel’s Optane solution is that most real world work actually takes place at a low queue depth, so this is where drive performance should be focused, rather than large sequential speeds which tend to be emphasised in marketing spiel. Unfortunately Intel discontinued its consumer product line for Optane on 14 January 2021, and attempts to purchase a drive in late February 2021 were unsuccessful. Whilst this was disappointing, further research showed that conventional SSDs should have improved input-output operations per second (IOPS) with higher queue depth (QD). If a higher queue depth can be utilised with a NAND-based SSD to increase the speed of data transfer, then possibly the latency advantage of Optane might not be missed?

What Exactly Is Queue Depth?

Queue depth the number of outstanding input-output (IO) operations that have yet to be processed. Consider reading of random data. For many single-threaded applications, an IO read request for a sequence of bytes is submitted to the storage device and the program will wait for the data to be returned before continuing. Under this scenario a conventional hard disk drive will need to move the read head to the location where the data is stored, and then the sequential read associated with the IO read request is carried out. The time taken to read is the latency associated getting the read head to the data location plus the sequential read rate multiplied by the number of bytes. Submitted IO requests in parallel to a hard disk drive does little to improve read times, although the drive can optimise to some extent through the disk buffer etc. Since the read head can only be in one physical location at a time, the IO operations will stack up in a queue of pending operations. The number of outstanding IO operations is referred to as the queue depth.

With a solid state drive there are no physical moving parts. Because there are several flash memory chips, if multiple IO requests are simultaneously issued, the drive controlled may be able to complete all those requests in parallel or at the very least optimise the IO requests so that the speed is increased. There is a limit to this, but generally, as queue depth increases, the IOPS for the drive will also increase.

Drive performance for IOPS can be benchmarked using Anvil’s Storage Benchmarks tool with random reads. This increases the queue depth by employing and increasing number of threads to issue IO requests in parallel. The drives used for testing within my system are:

- Conventional hard disk drive (Toshiba PC P300 2TB)

- SATA III solid state drive (Crucial MX300 525GB)

- M.2 NVMe solid-state drive (Western Digital SN850 500GB)

The NVMe drive is currently the fastest NAND-based flash drive available. In theory the WD SN850 can reach random read speeds of 1,000,000 IOPS, which exceeds the random read for the Intel Optane 800P of 250,000 IOPS. Whilst this is a PCIe Gen4 drive, it is installed in a M.2 slot with 4x PCIe Gen3 lanes. This will limit the absolute maximum sequential speeds attainable, but for our use case involving multiple random reads, there should be plenty of headroom. In addition online results published for Intel Optane 800P 118GB drive are included for comparison. The results are shown in Figure 1.

Source: Legit Reviews (Optane)

Unsurprisingly we see that the solid state drives are head and shoulders above the hard disk drive in performance, with Intel’s Optane technology leading the way. Interestingly the hard disk drive performance does increase slightly with higher queue depths, but the improvements are more pronounced with solid state drives where the IOPS increases by over an order of magnitude. What is of most interest is that the solid state drives at QD16 and above exceed the Optane performance at QD1. This suggests that use of parallel IO with NAND-based flash drives should be able to achieve Optane-like performance levels for single-threaded IO.

Libraries Tested to Implement HDF in Java

There are several different libraries available for reading and writing HDF5 files with Java. Three different libraries have been tested and compared:

- The Java Native Interface (JNI) wrappers for the official HDF5 library

- The HDF5 query language which also uses a JNI wrapper

- The jHDF library written using pure Java

Various code snippets for reading and writing using each of these libraries was written and tested whilst exploring the potential for the HDF5 format as an internal format to substitute instead of SEG-Y. The comparison between the different libraries can be summarised as follows:

| Library | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| HDF5 JNI | - Official distribution for HDF5 format - Extensively tested and actively maintained |

- Requires native code for each target platform - Single-threaded implementation for reading hyperslabs - Low level code is harder to implement |

| HDFql | - Uses standardised query language to interact with HDF5 file - High level code is cleaner and easier to understand |

- Limited debugging information available if queries are incorrectly formed - Writing of attributes and datasets, reading of attributes successfully tested, but reading of datasets would not work during testing - Requires POSIX-style paths which makes it hard to access files not on C:\ drive in Windows |

| jHDF | - Pure Java implementation allows all IDE debugging and profiling tools to be used - Can implement parallel reading of individual chunks |

- Niche library with limited features implemented - Cannot write HDF5 files - Not as widely adopted as other libraries - No method for reading hyperslabs implemented (custom code required) |

No library is sufficient for the purposes of Pyrus on its own. The jHDF library is attractive because it is written in pure Java and therefore integrates better with the rest of the codebase. In particular, it is possible to write a parallel algorithm for reading of chunks in a hyperslab. This approach could be used to increase the queue depth. However, jHDF does not implement writing of HDF files so either the HDF5 JNI wrapper library or HDFql will be required to implement this functionality. Generally HDFql is preferred as it is simpler to read once successfully coded. However, it has proven harder to debug during development and the low-level HDF5 JNI, whilst tedious and unwieldy, at least gives an indication as to where problems might exist. Case in point is that I was unable to get my implementation of HDFql for reading files to work and it was felt that time spent on investigating the reasons why the code was failing would be better invested into developing working code with other libraries.

Implementing Parallel IO with HDF5

Using the HDF5 library with the Java Native Interface (JNI) wrapper allows the basic single threaded performance to be tested. This is the reference library implementation and uses native code. The easiest way to increase the queue depth with a solid state drive is to issue multiple IO requests for each chunk in parallel. This can be achieved with the jHDF library and the io.jhdf.api.dataset.ChunkedDataset.getRawChunkBuffer() method.

A code snippet showing an implementation for reading hyperslabs from a File with variable name source_file is shown below:

/**

* Reads a hyperslab defined as a plane between two points in space. Currently only inline, crossline and slice

* planes are supported where the type of plane is determined by testing for equality of the x, y and z values for

* each point. Constant x implies inline, constant y implies crossline and constant z implies slice. This method

* implements the native HDF5 JNI wrappers and the jHDF library which is a pure Java implementation for reading HDF

* format files. Use of the jHDF library allows parallel reading of chunks to be requested which can improve IO

* speed for certain chunk sizes on some device types.

*

* @param v1 integer array {x, y, z} where x is inline number, y is crossline number and z is depth

* @param v2 integer array {x, y, z} where x is inline number, y is crossline number and z is depth

* @param use_parallel flags whether the jHDF library should be used with parallel chunk reading

* @return 1-dimensional float array representing 2D plane with stride = depth or inline depending on plane

* @throws java.io.IOException

*/

public float[] readHyperslab(int[] v1, int[] v2, boolean use_parallel) throws IOException {

// Define corner points of the hyperslab and determine type of plane to be read

int x1 = Math.min(v1[0], v2[0]) - min_il;

int x2 = Math.max(v1[0], v2[0]) - min_il;

int y1 = Math.min(v1[1], v2[1]) - min_xl;

int y2 = Math.max(v1[1], v2[1]) - min_xl;

int z1 = Math.min(v1[2], v2[2]);

int z2 = Math.max(v1[2], v2[2]);

int nx = x2 - x1 + 1;

int ny = y2 - y1 + 1;

int nz = z2 - z1 + 1;

// Initialise output float array and check for orthogonality

float[] fb;

final Plane plane;

if (x1 == x2) {

plane = Plane.INLINE;

fb = new float[ny * nz];

} else if (y1 == y2) {

plane = Plane.CROSSLINE;

fb = new float[nx * nz];

} else if (z1 == z2) {

plane = Plane.SLICE;

fb = new float[nx * ny];

} else {

plane = null;

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Hyperslab is not orthogonal");

}

LOG.log(Level.FINER, "Reading hyperslab {1} -> {2} from internal HDF file {0} using {3}",

new Object[]{source_file.getName(), ArrayUtils.toString(v1), ArrayUtils.toString(v2),

use_parallel ? "jHDF version: 0.6.1" : String.format("HDF5 JNI version: %d.%d.%d",

H5.LIB_VERSION[0], H5.LIB_VERSION[1], H5.LIB_VERSION[2])

});

/*

* If parallel reading has not been requested, then the read method reverts to the HDF5 JNI native library.

*/

if (!use_parallel) {

// Allocate array of pointers to two-dimensional arrays (the elements of the dataset)

long file_id = -1;

long dataset_id = -1;

long dataspace_id = -1;

long memspace_id = -1;

try {

// Open file using the default properties

file_id = H5.H5Fopen(source_file.getCanonicalPath(), H5F_ACC_RDONLY, H5P_DEFAULT);

// Open dataset using the default properties

if (file_id >= 0) {

dataset_id = H5.H5Dopen(file_id, "seismic_dataset", H5P_DEFAULT);

}

// Define and select the hyperslab to use for reading

if (dataset_id >= 0) {

dataspace_id = H5.H5Dget_space(dataset_id);

// Define the hyperslab using start indices in x, y, z and the size of the hyperslab extent (count)

long[] start = {x1, y1, z1};

long[] stride = null;

long[] count = {nx, ny, nz};

long[] block = null;

// Read the data using the previously defined hyperslab

if (dataspace_id >= 0) {

H5.H5Sselect_hyperslab(dataspace_id, H5S_SELECT_SET, start, stride, count, block);

memspace_id = H5.H5Screate_simple(3, count, null);

if (memspace_id >= 0) {

H5.H5Dread(dataset_id, H5T_NATIVE_FLOAT, memspace_id, dataspace_id, H5P_DEFAULT, fb);

}

H5.H5Sclose(memspace_id);

}

}

} catch (HDF5Exception | IllegalArgumentException | NullPointerException ex) {

LOG.log(Level.SEVERE, "Problem while reading hyperslab from HDF file: {0}", ex.getMessage());

Exceptions.printStackTrace(ex);

}

// Close dataset and file

try {

if (dataset_id >= 0) {

H5.H5Dclose(dataset_id);

}

if (dataspace_id >= 0) {

H5.H5Sclose(dataspace_id);

}

if (file_id >= 0) {

H5.H5Fclose(file_id);

}

} catch (HDF5LibraryException ex) {

LOG.log(Level.SEVERE, "Failed to properly close HDF file {0}: {1}",

new Object[]{source_file.getName(), ex.getMessage()});

Exceptions.printStackTrace(ex);

}

return fb; // HDF5 JNI method concluded; return float array

}

/*

* Open our HDF file and directly access chunk data. Each chunk is accessed in parallel which improves the queue

* depth for solid state devices and can thus increase the input-output operations per second (IOPS). Float data

* is converted directly from the byte buffer and written to output float array only for the data needed. This

* reduces unnecessary copies and thus speeds up the performance of this method. Workflow to read a hyperslab is

* as follows:

* (1) Work out which chunks the v1 and v2 corner points fall within

* (2) Determine the chunk index number and chunk offset (upper-top-left) corner for the first and last

* chunks.

* (3) Create an array of all chunks that will be needed. For each chunk store the sub-plane of values that

* must be read from that chunk and the mapping of those values into the hyperslab co-ordinates.

* (4) Parallel read all the chunks in the chunk array and get the float values from the float buffer of

* each chunk and copy into the output float array.

*/

try (HdfFile hdfFile = new HdfFile(source_file)) {

Dataset dataset = hdfFile.getDatasetByPath("seismic_dataset");

if (dataset instanceof ChunkedDataset) {

ChunkedDataset chunked_dataset = (ChunkedDataset) dataset;

// Get the chunk size

final int[] chunk_size = chunked_dataset.getChunkDimensions();

// Calculate vector reference for the first chunk

int[] first_chunk_ref = new int[3];

first_chunk_ref[0] = x1 / chunk_size[0];

first_chunk_ref[1] = y1 / chunk_size[1];

first_chunk_ref[2] = z1 / chunk_size[2];

// Calculate vector reference for the last chunk

int[] last_chunk_ref = new int[3];

last_chunk_ref[0] = x2 / chunk_size[0];

last_chunk_ref[1] = y2 / chunk_size[1];

last_chunk_ref[2] = z2 / chunk_size[2];

// Work out how many chunks are required along each axis and create an array of chunks

int[] chunkslab_dim = new int[]{

last_chunk_ref[0] - first_chunk_ref[0] + 1,

last_chunk_ref[1] - first_chunk_ref[1] + 1,

last_chunk_ref[2] - first_chunk_ref[2] + 1};

int nchunks = chunkslab_dim[0] * chunkslab_dim[1] * chunkslab_dim[2];

int[][] chunk_offset = new int[nchunks][3];

int[][] chunk_src_pos = new int[nchunks][3];

int[][] chunk_src_len = new int[nchunks][3];

int[][] chunk_dst_pos = new int[nchunks][3];

int c = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < chunkslab_dim[0]; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < chunkslab_dim[1]; j++) {

for (int k = 0; k < chunkslab_dim[2]; k++) {

// Reference location for each chunk as offset for the upper-top-left corner

chunk_offset[c][0] = (first_chunk_ref[0] + i) * chunk_size[0];

chunk_offset[c][1] = (first_chunk_ref[1] + j) * chunk_size[1];

chunk_offset[c][2] = (first_chunk_ref[2] + k) * chunk_size[2];

// {x, y, z} offset within chunk to start reading from

chunk_src_pos[c][0] = x1 < chunk_offset[c][0] ? 0 : x1 - chunk_offset[c][0];

chunk_src_pos[c][1] = y1 < chunk_offset[c][1] ? 0 : y1 - chunk_offset[c][1];

chunk_src_pos[c][2] = z1 < chunk_offset[c][2] ? 0 : z1 - chunk_offset[c][2];

chunk_dst_pos[c][0] = chunk_offset[c][0] + chunk_src_pos[c][0] - x1;

chunk_dst_pos[c][1] = chunk_offset[c][1] + chunk_src_pos[c][1] - y1;

chunk_dst_pos[c][2] = chunk_offset[c][2] + chunk_src_pos[c][2] - z1;

// Datermine size of the hyperslab within the chunk and set lengths for data to be read

// depending on whether the hyperslab has an end within the chunk or completely traverses it

if (x2 < chunk_offset[c][0] + chunk_size[0]) {

if (x1 >= chunk_offset[c][0]) {

chunk_src_len[c][0] = x2 - x1 + 1; // start and end positions are both within chunk

} else {

chunk_src_len[c][0] = x2 - chunk_offset[c][0] + 1; // end within chunk

}

} else {

if (x1 >= chunk_offset[c][0]) {

chunk_src_len[c][0] = chunk_size[0] - chunk_src_pos[c][0]; // start within chunk

} else {

chunk_src_len[c][0] = chunk_size[0]; // full span of chunk

}

}

if (y2 < chunk_offset[c][1] + chunk_size[1]) {

if (y1 >= chunk_offset[c][1]) {

chunk_src_len[c][1] = y2 - y1 + 1; // start and end positions are both within chunk

} else {

chunk_src_len[c][1] = y2 - chunk_offset[c][1] + 1; // end within chunk

}

} else {

if (y1 >= chunk_offset[c][1]) {

chunk_src_len[c][1] = chunk_size[1] - chunk_src_pos[c][1]; // start within chunk

} else {

chunk_src_len[c][1] = chunk_size[1]; // full span of chunk

}

}

if (z2 < chunk_offset[c][2] + chunk_size[2]) {

if (z1 >= chunk_offset[c][2]) {

chunk_src_len[c][2] = z2 - z1 + 1; // start and end positions are both within chunk

} else {

chunk_src_len[c][2] = z2 - chunk_offset[c][2] + 1; // end within chunk

}

} else {

if (z1 >= chunk_offset[c][2]) {

chunk_src_len[c][2] = chunk_size[2] - chunk_src_pos[c][2]; // start within chunk

} else {

chunk_src_len[c][2] = chunk_size[2]; // full span of chunk

}

}

c++; // move onto the next chunk

}

}

}

/*

* To improve reading speed we attempt to increase the queue depth for pending operations with the disk.

* This is done using multiple threads to read each chunk in a separate thread. The method will block

* until all worker threads have completed.

*/

// Process chunks to extract data that lie on the hyperslab plane

LOG.log(Level.FINEST, "Processing {0} chunks of size {2} for {1}",

new Object[]{nchunks, plane.toString(), ArrayUtils.toString(chunk_size)});

// Read the data using the previously defined hyperslab stripes

final CountDownLatch flag = new CountDownLatch(nchunks);

final AtomicInteger aj = new AtomicInteger(); // loop from initial aj

final int nj = nchunks; // loop up to nj - 1

Thread[] worker = new Thread[num_threads];

for (int thread = 0; thread < worker.length; ++thread) {

worker[thread] = new Thread(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

for (int ac = aj.getAndIncrement(); ac < nj; ac = aj.getAndIncrement()) {

// Create a memory-mapped float buffer to the data in this chunk

ByteBuffer raw_chunk_buffer = chunked_dataset.getRawChunkBuffer(chunk_offset[ac]);

FloatBuffer raw_fb = raw_chunk_buffer.order(ByteOrder.nativeOrder()).asFloatBuffer();

// Copy only the floats needed for the planar type into our destination float array

int src_pos, dst_pos; // position indices within chunk and float array

src_pos = chunk_src_pos[ac][0] * chunk_size[1] * chunk_size[2]

+ chunk_src_pos[ac][1] * chunk_size[2]

+ chunk_src_pos[ac][2];

switch (plane) {

case INLINE:

dst_pos = chunk_dst_pos[ac][1] * nz + chunk_dst_pos[ac][2];

// Iterate over chunk 'traces' at position y and copy into destination

for (int y = chunk_src_pos[ac][1];

y < (chunk_src_pos[ac][1] + chunk_src_len[ac][1]);

y++) {

int z = chunk_src_pos[ac][2];

raw_fb.position(src_pos

+ (y - chunk_src_pos[ac][1]) * chunk_size[2]

+ (z - chunk_src_pos[ac][2]));

raw_fb.get(fb, dst_pos, chunk_src_len[ac][2]);

dst_pos += chunk_src_len[ac][2];

dst_pos += nz - chunk_src_len[ac][2];

}

break;

case CROSSLINE:

dst_pos = chunk_dst_pos[ac][0] * nz + chunk_dst_pos[ac][2];

// Iterate over chunk 'traces' at position x and copy into destination

for (int x = chunk_src_pos[ac][0];

x < (chunk_src_pos[ac][0] + chunk_src_len[ac][0]);

x++) {

int z = chunk_src_pos[ac][2];

raw_fb.position(src_pos

+ (x - chunk_src_pos[ac][0]) * chunk_size[1] * chunk_size[2]

+ (z - chunk_src_pos[ac][2]));

raw_fb.get(fb, dst_pos, chunk_src_len[ac][2]);

dst_pos += chunk_src_len[ac][2];

dst_pos += nz - chunk_src_len[ac][2];

}

break;

case SLICE:

dst_pos = chunk_dst_pos[ac][0] * ny + chunk_dst_pos[ac][1];

// Iterate over chunk 'samples' at position (x, y) and copy into destination

for (int x = chunk_src_pos[ac][0];

x < (chunk_src_pos[ac][0] + chunk_src_len[ac][0]);

x++) {

for (int y = chunk_src_pos[ac][1];

y < (chunk_src_pos[ac][1] + chunk_src_len[ac][1]);

y++) {

raw_fb.position(src_pos

+ (x - chunk_src_pos[ac][0]) * chunk_size[1] * chunk_size[2]

+ (y - chunk_src_pos[ac][1]) * chunk_size[2]);

raw_fb.get(fb, dst_pos, 1);

dst_pos++;

}

dst_pos += ny - chunk_src_len[ac][1];

}

break;

default:

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Hyperslab is not orthogonal");

}

flag.countDown();

}

}

});

exec_pool.execute(worker[thread]);

}

// Block until all chunk reads have completed

try {

flag.await();

} catch (InterruptedException e1) {

LOG.severe(e1.getMessage());

}

return fb; // jHDF method concluded; return float array

} else {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Dataset is not chunked");

}

}

}

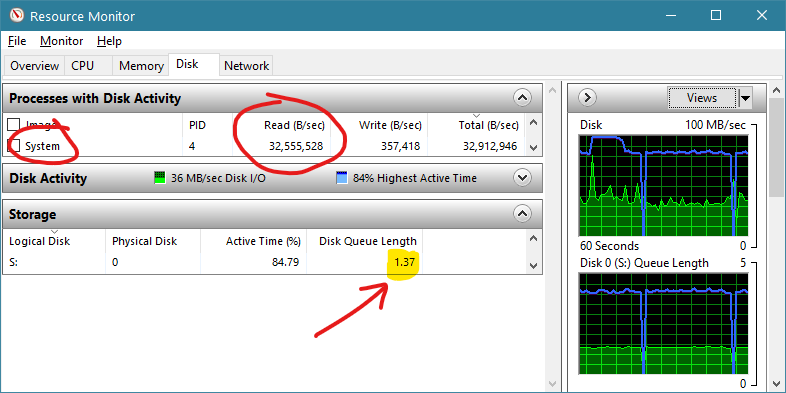

The IO read speed achieved using this code can be monitored using the built-in Resource Monitor in Windows 10.

As shown in Figure 2, using a SATA III SSD (drive letter S:) the HDF5 JNI approach exhibits the following performance whilst reading from our 1,966 x 1,103 x 3,001 test file. It can be seen that the active process associated with the file IO is ‘System’ which indicates native system calls are being used. Overall a read rate of about 32 million bytes per second is attained. The queue depth is barely above one in this case.

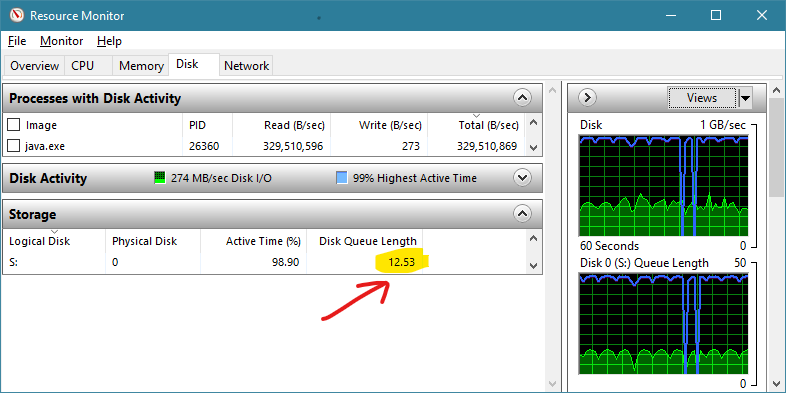

Switching to a parallel read method (with 16 threads) increases the queue depth to more than 12 as shown in Figure 3. The relevance of this can be seen immediately in the read speed which increases more than 10x to nearly 330 million bytes per second. The process associated with the file IO is now ‘java.exe’ indicating that the IO commands are now being issued from the Java Virtual Machine rather than through native system calls.

The results are in line with expectations from benchmarking. It is confirmed that parallel IO in Java can be used to increase queue depth and thus improve the effective read IO speed attained.

Thoughts on Chunk Sizing and Java HDF Libraries

A more thorough test of the parallel Java IO methods involves comparison between the following variables:

- Storage media e.g. hard disk drive / SATA III SSD / NVMe SSD

- HDF5 library used for reading e.g. HDF5 JNI / jHDF

- Chunk size used when writing HDF5 file

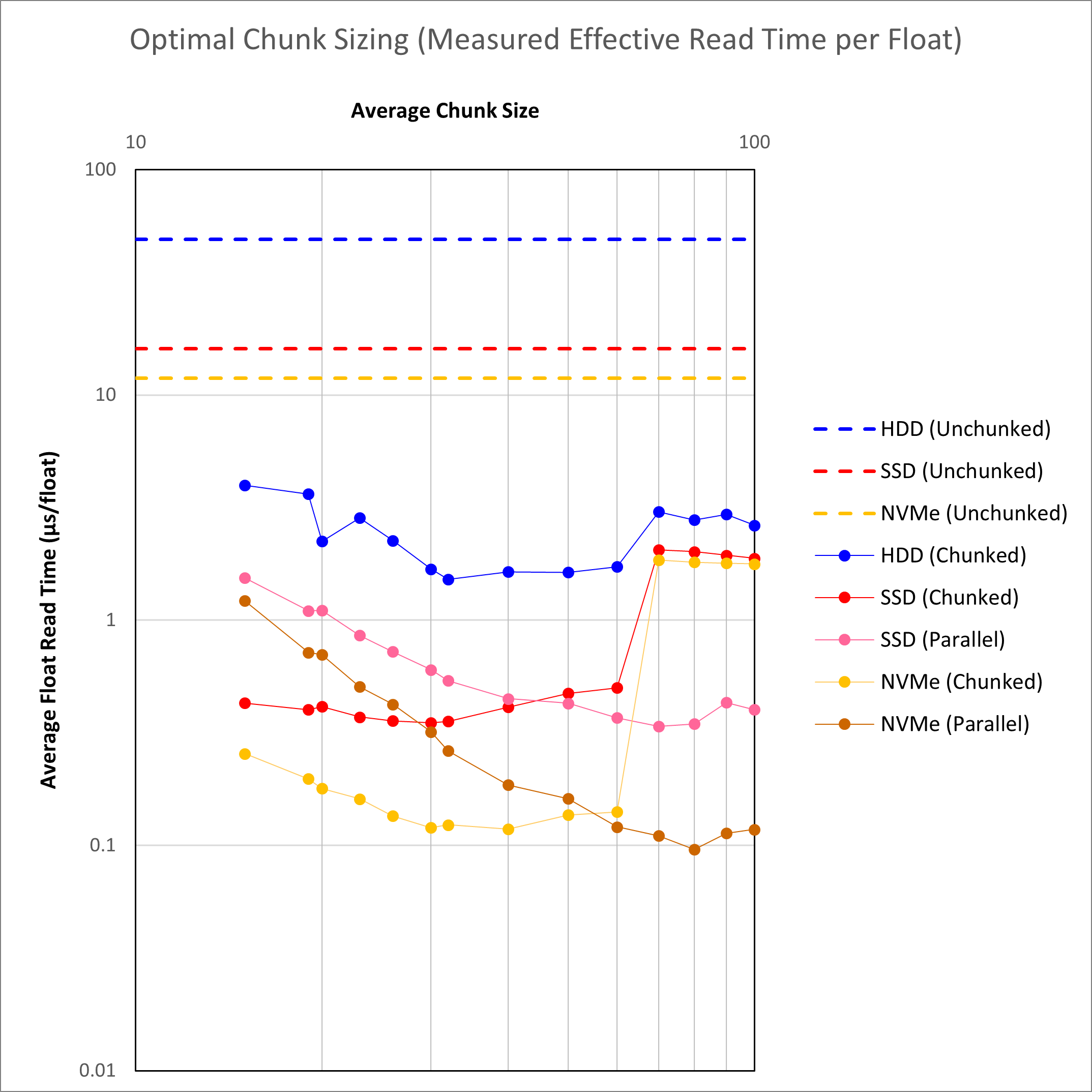

A series of HDF5 files were created with different chunk sizes and then tested with both the HDF5 JNI library (indicated as ‘Chunked’) and the jHDF library (indicated as ‘Parallel’). Parallel processing was conducted using 16 threads. The chunked read times are compared against the unchunked e.g. SEG-Y read times. For all cases the read time shown is the average of the inline, crossline and slice float read time.

When I set out on this investigation, it was hoped that the conclusion would be an unequivocal, “Approach X is best for the following reasons …”. The results are mixed and suggest that there is more than one way to obtain an acceptable result.

First and foremost, it is clear that chunking works. The average read time for a chunked dataset stored on a hard disk drive is faster than the same average read time for an unchunked dataset stored on an NVMe solid state drive. This is a positive improvement on the industry-standard SEG-Y format.

To achieve an average read time of <0.1 μs/float, which is needed to at least match inline read speeds for SEG-Y on a hard disk drive, it is clear an NVMe drive is needed. A cheaper SATA III SSD is definitely an improvement over a hard disk drive, but an NVMe drive is the only media that delivers a read time of <0.1 μs/float with the jHDF library.

A surprising discovery is that the HDF5 JNI and jHDF libraries switch places when it comes to outright read speed depending on the chunk size used. The reasons for this are not clear at the moment, and may be associated with an inefficient implementation of the parallel IO algorithm. In particular, at low chunk sizes, the jHDF library lags the performance of the HDF5 JNI library quite considerably, and the performance noticeably decreases as the chunk size diminishes. In contrast the HDF5 JNI library maintains a more stable performance. It is suspected that there is a performance cost associated with reading each chunks. With the smaller chunks there are a larger number of chunk reads required, and this might be increasing the overhead associated with the pure Java implementation that is not as pronounced with the native implementation.

With larger chunk sizes the jHDF library delivers the very best performance, and for chunk size more than 70 x 70 x 70 the HDF5 JNI library performance suffers. Again it is not known why this happens. It is observed that 1 MB (= 1,048,756 bytes) is equivalent to a chunk dimension of 64 where the data type is a single-precision floating point number of four bytes per sample. It appears that the HDF5 JNI library is not optimised to read chunks of this size or larger.

What approach should the Pyrus suite adopt for its internal format?

One solution would be to use a chunk dimension of ~50 which would yield acceptable performance irrespective of the library used as the read times for HDF5 JNI and jHDF are very similar at this chunk dimension. The downside is that these are not the absolute fastest speeds.

The alternative solution is to use a chunk dimension of ~80 with the jHDF library. This would deliver the fastest speeds where data is stored on an SSD. For data stored on hard drive the HDF5 JNI library would need to be employed where the performance is not optimal. On the other hand the chunked HDD speed would still be faster than the unchunked speed, and the performance for the HDF5 JNI library at a chunk dimension of more than 70 is not that much slower than the performance achieved with SSDs at for the same chunk dimension.

Overall, pandering to the edge case for reading from a HDD in today’s environment is counter-productive. The best performance is achieved with the jHDF library and because it is written in pure Java it will be easier to maintain.